Constantinople, Part 2: Refugees in Peril

By 1921, the Queen of Cities was inundated with refugees from Anatolia, the Caucasus, and Russia. Thousands of lives hung in the balance. What could Near East Relief do?

This is the second in a series of Dispatches on Near East Relief’s work in Constantinople (now Istanbul). You can read the first installment here.

DESPERATE FOR SHELTER

While most people remember Near East Relief for its work with orphans, Near East Relief also provided lifesaving care for adult refugees and displaced families in Constantinople. By April 1921, Near East Relief was one of several prominent international aid organizations working with approximately 102,000 refugees in Constantinople.

The severity of the refugee situation was due, in part, to a dire lack of housing throughout Constantinople. Much of the city’s available housing stock had been destroyed by frequent fires, creating a shortage of homes for natives of Constantinople long before the first refugees arrived. The city was wholly unprepared to house more than 100,000 newcomers.

Above: A panoramic view of Constantinople in the 1880s. Public domain image.

The refugees tended to settle in communities with people from their own regions. Some 7,000 Russian refugees were lucky enough to obtain housing through the Russian Embassy, but far more lived in wooden barracks and tents. The Russian refugee community at Touzla received considerable support from the British government.

The Armenian refugee community was distributed between 6 large camps. Although they were called refugee camps, these were urban settlements. Most Armenian refugees in Constantinople lived in former barracks or converted schools rather than tents. The Armenian refugees received free lodging, but there were no guarantees of food, bedding, or clothing.

About 5,00 Greek refugees lived in two large houses in Beshiktash, while smaller groups found shelter in local schools and churches — even private homes. By late 1922, many Greeks had migrated to the new farm colony in Rodosto. Near East Relief also operated a small camp for 715 Georgian refugees at Anatoli Kavak. The Jewish Joint Distribution Committee operated four enormous “boarding houses” for Jewish refugees in Ortakoy. The largest of these houses had the distinction of serving one hot meal per day (usually soup).

Left: Refugee children in Stamboul. From Constantinople To-Day, 1922.

A baker in front of the "American Bakery," which advertised its wares in six languages: Armenian, Ladino, English, Ottoman Turkish, Greek, and Russian. Ortakoy, Constantinople, 1922. Library of Congress.

FOOD FOR REFUGEES

Refugees of all backgrounds relied heavily on soup kitchens and food vouchers supplied by the Allied governments. These paper tickets were exchanged for free meals. Very little food was available to adult refugees. In mid-1921 the French government was forced to stop providing food relief to Russian refugees in Constantinople; it had exhausted its resources. By July, the American Red Cross was threatening to withdraw from Constantinople due to a lack of supplies. Ultimately, the Red Cross leadership appropriated emergency funds in order to continue its work in the region.

Initially, Near East Relief provided half a loaf of bread per person per day in the Armenian camps. Even this proved to be a considerable strain on the organization’s resources. Near East Relief focused on providing bread and coal to widows with children; refugee children under the age of 7 also received milk.

Despite the efforts of multiple governments and relief organizations, Near East Relief Managing Director H.C. Jaquith estimated that, by May 1922, 30 refugees were dying of starvation in Constantinople every day.

EARNING A LIVING

For most of its history, Constantinople had been an important trading hub between East and West. Prolonged conflict and military action had a strong negative effect on the city’s economy. Like many trade centers, Constantinople focused on the distribution of goods rather than their creation. The city had never developed a strong manufacturing sector — an industry that traditionally employs migrants and refugees. Constantinople natives were also struggling to find work.

Near East Relief provided employment for some refugee women in its local “Fabrica,” or textile factory. The women produced traditional fabrics, including lavishly embroidered clothing and linens for the home. Russian cross-stitch and Armenian lace proved especially popular.

Despite ongoing unrest in the Near East, Constantinople was slowly regaining its reputation as a tourist destination. Near East Relief took advantage of the waves of incoming tourists to publicize the organization’s work. Tourists were encouraged to buy exotic souvenirs at the Near East Industries store. Some cruise ships even placed Near East Relief donation coupons in each ship cabin to encourage travelers to make a useful gift.

Left: A Russian refugee renowned for her embroidery graced the cover of a Near East Industries catalog, c. 1921.

Unfortunately, Near East Relief was only able to employ a small percentage of refugee women. Other organizations helped to place women and girls in domestic positions, but there was limited demand. Most refugee women, regardless of ethnic background, found work as laundresses and cleaners. It was grueling, backbreaking work for women who were largely unaccustomed to physical labor.

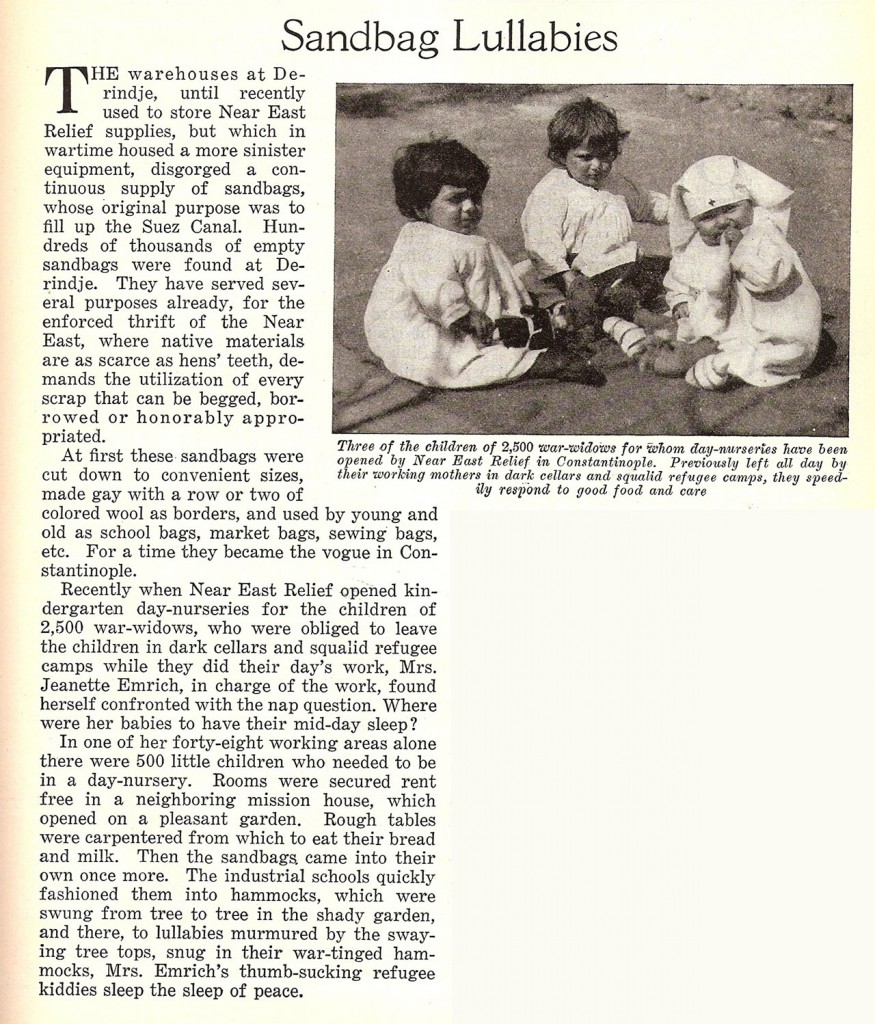

When refugee women entered the work force, they were faced with a new question: what could they do with their children while they worked? Many women were forced to leave their young children at home, unattended. When Near East Relief workers discovered that some children were being drugged and left alone during the work day, they came up with a pioneering solution.

Near East Relief day nurseries were a precursor to the modern day care center. Children were dropped off at the day nursery in the morning. They received food and enjoyed a safe place to play and sleep. Mothers picked up their children at the end of the work day. In July 1922, Near East Relief worker Jeanette Emrich reported that the day nursery system allowed 2,500 refugee mothers to work outside of the home. Most women used their income to buy additional food such as rice, olives, and yogurt.

Right: The cover of this Near East Industries catalog (c. 1921) was a work of art in its own right. The stylized text reads “Constantinople.”

...One must record the great strength and heroism of these Armenian women who have suffered everything . . . who have no definite hope for themselves or for their country. Yet they carry on, sending their children to school, toiling at unaccustomed and difficult tasks, keeping their families together against fearful odds. It is heroism which must bear fruit in the character of their children.

NER nurse Frances MacQuaide trained 14 Armenian women to provide medical care in refugee communities. The New Near East magazine, Sept. 1922.

FIGHTING DISEASE

With so many refugees living in such close quarters, communicable diseases spread at an alarming rate. Near East Relief doctors and nurses traveled from one camp to the next to provide medical care to adults and children. The organization estimated that it provided 22,476 medical treatments per month to patients in Constantinople.

In addition to camp visits, Near East Relief operated two specialized hospitals: one for trachoma in Boyadjikoy, and one for tuberculosis in Yedi Koule. Four American and 29 local nurses ran 44 child welfare clinics for refugee mothers. These clinics treated 2,000 children per month and provided the mothers with important health instruction.

Refugee women working at the Near East Relief Industrial Department in Constantinople. The New Near East magazine, Feb. 1922.

The lack of food was particularly taxing for young bodies. From January to April 1921, more than half of the medical treatments rendered to refugee children were the result of malnutrition rather than disease.

Nurse Frances MacQuaide used education as a tool to prevent disease. MacQuaide recruited 14 Armenian refugee women, all of whom were graduates of American schools in Turkey, and trained them as medical workers. The young women traveled to the camps with medical supplies, sanitation instructions, and milk for the children. This small group of women provided invaluable medical care to the ever-growing refugee community.

It must have seemed as if life in Constantinople could not possibly get any more difficult. But in late 1922, things took a horrible and unexpected turn.

Check back soon for the next installment in this series of Dispatches.