Constantinople: Queen of Cities

They called it the crossroads of Europe and Asia. The golden city on the Bosphorus had it all: wealth, beauty, diversity . . . and a burgeoning refugee crisis. This is the first in a series of Dispatches on Near East Relief’s work in Constantinople (now Istanbul).

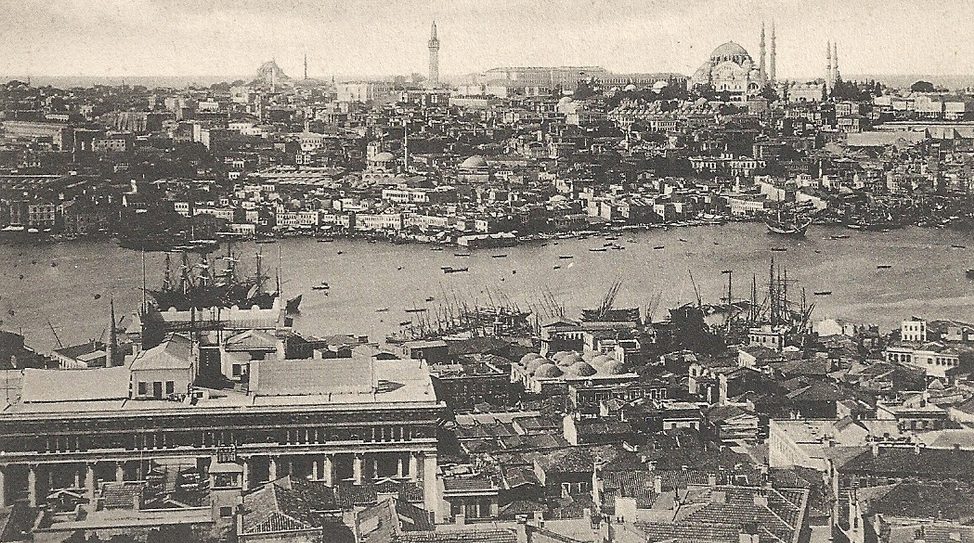

Panoramic view of Constantinople in the late 1800s. Public domain image.

WHERE THE CONTINENTS MEET

Constantinople. In the early 20th century, the very name conjured up images of an exotic metropolis. Constantinople was a multicultural center at the literal crossroads of Europe and Asia. The Bosphorus (also known as the Strait of Constantinople), which forms the boundary between the continents, divided Constantinople in half: one side European, the other Asian.

Over the course of its long history, Constantinople had been part of the Greek, Persian, Byzantine, Roman, and Ottoman Empires. The vibrant trading center was a melting pot of Turkish, Greek, Armenian, and Jewish culture. It was also a popular destination for tourists from all over the world.

*The city has been known as Istanbul since 1923.

A CENTER FOR TRADE AND CULTURE

Once the seat of Orthodox Christianity, Constantinople still boasted many beautiful churches belonging to numerous Christian denominations. The various synagogues throughout the city were evidence of a thriving Jewish community that traced its roots to the expulsion from Spain.

These houses of worship existed in close proximity to Ottoman mosques, including the famously beautiful imperial Blue Mosque and Hagia Sophia (a pre-Ottoman Christian church). Non-Muslims (dhimmi) in Constantinople enjoyed freedom of religion, but they had far fewer legal rights than their Muslim neighbors. The same was true throughout the Empire. Interestingly, Muslims only accounted for about half of the city’s population.

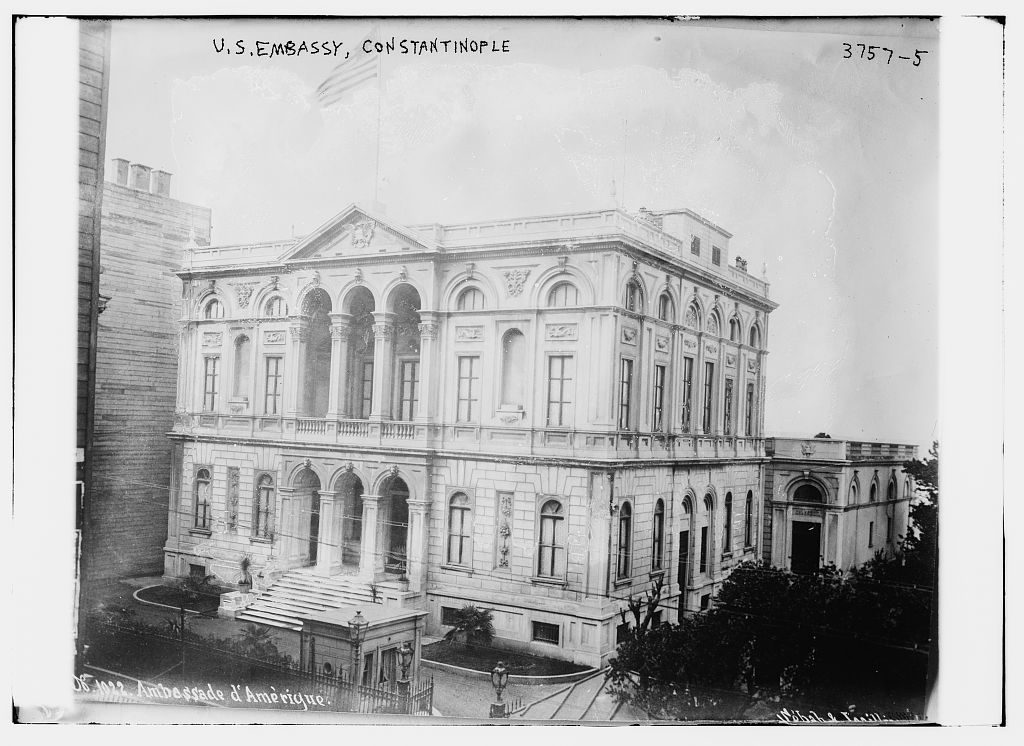

Constantinople was the capital of the Ottoman Empire. As a modern city, it had its share of amenities and architectural wonders. The city boasted the Topkapi Palace, which was the residence of the Sultan, and the Sublime Porte — the seat of government for the Empire. Many countries, including the United States, had embassies in Constantinople. Opulent palaces dotted the banks of the Bosphorus. The capital maintained an air of elegance and prosperity as the Ottoman Empire slowly declined.

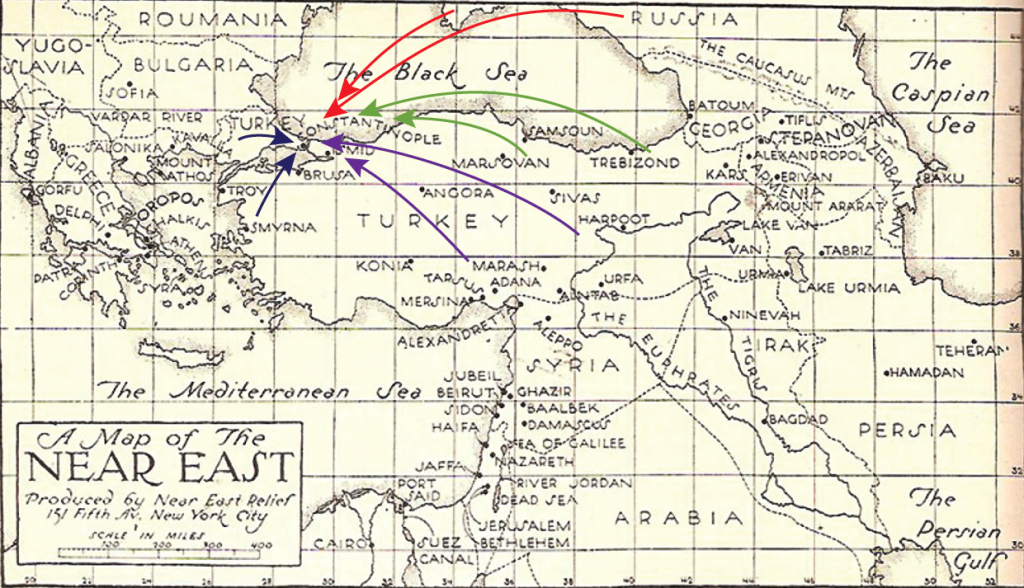

Map of Constantinople from Historical Atlas by William Shepard, courtesy of University of Texas at Austin.

All roads from Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Southern Russia as far as the Volga, and from all the Balkan States, lead to Constantinople.

View of Constantinople, 1909. Library of Congress.

CONFLICT AND CRISIS

World War I hit Constantinople hard. Military violence and government-orchestrated massacres drove countless refugees to the city. The Ottoman government and the Allied Forces signed the Armistice of Mudros in October 1918, ending the Empire’s involvement in World War I.

British and French troops took control of Constantinople. The Allies opened the former imperial territories to foreign travelers. This meant that groups like Near East Relief could send relief workers into Turkey for the first time since the beginning of World War I.

At the same time, Mustafa Kemal and other members of the former Ottoman military were launching the Turkish National Movement. The Kemalist army attacked Allied troops and Christian settlements throughout Anatolia. These renewed hostilities gave rise to yet another massive wave of refugees, desperate for safety in the struggling city of Constantinople.

Patterns of refugee migration to Constantinople in 1920 and 1921. Red represents Russian refugees, green represents Greeks, purple represents Armenians, and blue represents Turks. Refugees traveled by land and water.

REFUGEES IN A SUFFERING CITY

According to Constantinople To-day; Or, the Pathfinder Survey of Constantinople, a 1922 joint publication coauthored by eight aid organizations working in the city, an estimated 101,955 refugees were living in Constantinople by April 1921.

The American Red Cross reported that 65,000 Russian refugees had fled from the east. They traveled to escape a political revolution and a devastating famine in South Russia. Most of the Russian refugees came from Odessa, Novorossisk, and Crimea. The American Red Cross focused its work on these Russian refugees, with considerable assistance from French and British organizations.

The American Red Cross further estimated that roughly 27,000 Turkish refugees had flocked to Constantinople from territories in the grip of the Greco-Turkish War: Thrace to the west, and Smyrna to the southwest. The Turkish Red Crescent estimated that there were closer to 50,000 Turkish refugees in Constantinople.

There is in Constantinople the difficulty of language and custom, for in a single half hour...one can hear at least 30 languages spoken. Here East meets West and the ancient camel may be caught in the same photograph with the 1921 Ford automobile.

Refugee girl in front of a makeshift tent, Constantinople, c. 1920.

Aid organizations believed that 5,000 Greek refugees had traveled to Constantinople from the Black Sea region of Anatolia, including Samsoun and Trebizond. They fled the advancing Turkish Nationalist Army. An estimated 3,200 Armenian refugees came to Constantinople in 1920 and 1921. They traveled from the far eastern reaches of Anatolia and from the Cilicia region, which was no longer under French military protection.

It is worth noting that it was extremely difficult to classify refugees. Some groups had been in Constantinople for almost a decade and had achieved a certain level of self-support compared to other refugees. The problem of refugee classification persists in today’s crisis.

The refugees had mainly come to Constantinople with the intention of traveling to other countries, or returning home when the danger subsided. But other countries had closed their doors, and the violence showed no sign of abating. Constantinople was congested with people who had nowhere else to go. Disease was rampant. Education was nonexistent. Starvation soon became a way of life. And the city had another major problem: thousands upon thousands of orphaned children.

It was a seemingly impossible humanitarian crisis. What could Near East Relief do to help?

This is the first in a series of Dispatches on Near East Relief’s work in Constantinople. Check back soon for the next installment.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE NEAR EAST FOUNDATION'S WORK TODAY

The Palazzo Corpi was the United States Embassy to the Ottoman Empire. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau worked in this palatial building in the Pera district (now Beyoglu). Library of Congress, c.1915.