Susan B. Anthony’s Nieces and Near East Relief

On International Women’s Day, the Near East Relief Historical Society is excited to share the story of Gertrude and Amy Anthony, nieces of suffragist Susan B. Anthony. The following dispatch is done in collaboration with Vicken Babkenian, an independent researcher for the Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. He is the co-author (with Prof. Peter Stanley) of Armenia, Australia and the Great War (NewSouth Publishing, 2016), which was shortlisted in two major Australian literary awards.

**************

The Hamidian Massacres and the first Armenian Relief Effort

When the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief (later known as Near East Relief) was formed to provide aid to Armenian genocide survivors in 1915, it was not the first time that Americans mobilized for international relief. Some 20 years before, a major relief effort was launched in America to help save the survivors of the Hamidian Massacres, also known as the Armenian Massacres of 1894-1896. Conservative estimates place the death toll at around 80,000, while the highest estimates propose that over five hundred thousand died. Hundreds of thousands more were left destitute, homeless, and in desperate need of aid.

This first relief effort, often overshadowed by its much larger successors and the formation of formal relief organizations, coincided with the rising tide of the first wave of the women’s movement and feminism in the west. Women were increasingly propelled into and inspired to join internationalism by an innate identification with victimized women elsewhere.

Image Left: Victims of a massacre of Armenians in Erzerum, W.L. Sachtleben, October 30, 1895

American women’s organizations were especially important in providing support for the Armenian relief movement. The National Council of Women of the United States passed a resolution in 1895 which stated:

That we deplore the outrages committed upon the Armenians, and record our appreciation of the unflinching heroism of our Armenian sisters in sacrificing their lives in defense of their honor and freedom of conscience, and we earnestly urge our sisters in Great Britain and other countries of Europe to use their Influence with their governments that they take immediate action to establish security of life, honor and property in Armenia.

Championing the Armenian cause were many habitual humanitarians and well-known American women activists including, Julia Ward Howe of the American Women’s Suffrage Association and Frances Willard, leader of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Willard argued that the ‘American spirit and example’ had ‘stimulated the Armenian spirit of independence’ that led to their repression. It was therefore an American ‘duty’ to provide aid to the Armenians. In 1896, Willard cut short a cycling vacation in northern France to help provide aid to Armenian survivors who had found refuge in Marseille. Many more American women missionaries, who had been stationed throughout the Ottoman Empire, were able to provide direct relief to the victims. They were joined in March, 1896 by the first president of the American Red Cross (ARC) Clara Barton, who headed an ARC mission to the Empire.

The American humanitarian response to the Hamidian Massacres of the 1890s became a dress rehearsal for the much larger and well organized relief effort in response to the World War One (WWI) Armenian Genocide. American women mobilized, this time in greater numbers, to help Near East Relief (NER) provide relief to victims of a larger catastrophe – the Armenian Genocide.

Near East Relief

During WWI, about 170 American missionaries – many of them women – remained at their posts in isolated and remote areas of the Ottoman Empire. They included Mary Graffam at Sivas, Grace Knapp at Bitlis, Ida Stapleton at Erzerum, Ruth Parmalee at Harput, Elvesta Leslie at Urfa, Clara Richmond at Talas, Harriet Fischer at Adana, Elizabeth Ussher at Van, Emma Cushman at Konia, and many more. Despite being restrained from large-scale efforts by Ottoman authorities, the missionaries were able to provide limited relief and sanctuary to thousands of Armenian refugees. These limitations began to be lifted with the war’s end, greatly increase relief capacity effectiveness.

Image Right: ‘Cablegram’ pamphlet with quotations from religious and civic leaders. The inner cover features a statement from President Woodrow Wilson, c. 1919.

The armistice which ended the war with the Ottoman Empire opened opportunities to send reinforcements of personnel and supplies to missionary outposts scattered throughout the former Empire. British and French military leaders in the occupied territories of Turkey acknowledged the usefulness of NER due to its ‘complete organization’ and its workers ‘familiar[ity] with the language and habits of the people of the country’, With the support of President Woodrow Wilson, NER launched an ambitious citizen-based philanthropy campaign to raise $30 million to meet the urgent needs of the Armenian refugees. The equipment of fifteen army hospitals in France, no longer needed in peace time, were handed over to NER for a nominal sum. Newly acquired equipment included beds, surgical instruments, sterilizers, and medicines. Motor trucks, formerly used for carrying shells and soldiers to the front, were also turned over to the committee for use ‘in bringing back to their homes the deported refugees and for distributing food throughout the starving districts’.

Image Left: Magazine cover, American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, c. 1919

The Leviathan

In the first months of 1919, a ‘flotilla of ships’, including the freighters Mercurius, Leviathan, and Pensacola, set sail for the Middle East from New York. Described by the New York Times as the ‘largest contingent of missionaries, doctors, and relief workers ever sent overseas on such a mission’, the Leviathan alone carried over 240 people with equipment for fifteen hospitals – food, clothing and portable buildings – as well as sixty motor trucks and other material worth over $3.5 million. Passengers included five doctors from the American Women’s Hospitals, an organization established during the war to mobilize American women doctors for war service (after the War Department had declined to use them).

The Leviathan transported the first large group of Near East Relief volunteers in Feb. 1919. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Bain Collection.

Among the relief workers on the Leviathan were two sisters from Berkeley, California: Gertrude Anthony (aged 46), a teacher of biology and botany and Amy Anthony Burt (aged 50), a trained nurse. They were nieces of the famous American Woman Suffragist Susan B. Anthony, for whom the Nineteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution, which guaranteed women the right to vote in 1920, is colloquially named after.

The Leviathan reached Constantinople in March 1919. NER soon established a large network of hospitals, orphanages, and feeding stations for the Armenian refugees which extended from the Adriatic to the Caucasus and from Syria to Palestine. A number of ‘neutral houses’ were also established which gave sanctuary to Christian women and children who had been released from captivity as a result of WWI armistice terms.

Washington Post Article about Near East Relief Personnel, c. 1919. The article makes special notice of the fact that the relief workers on board were 'chiefly women', demonstrating an early acknowledgement of the invaluable work done by women relief workers for Near East Relief.

A group of women either before or after boarding the Leviathan, c. 1919.

Gertrude and Amy Anthony

Amy Anthony was assigned to the large boys’ orphanage at Kooleli, Constantinople (now Istanbul). Situated on the Asiatic side at the edge of the Bosphorus, The Kooleli Orphanage housed about 1,000 orphans, most of whom were Armenian. Gertrude Anthony was assigned to the Caucasus, where she worked in the capital of the First Armenian Republic, Erivan (also known as Yerevan).

Image Right: Gertrude and Amy Anthony, c. 1919.

In a letter from Erivan dated December 26, 1919, Gertrude describes the desperate situation of the Armenian refugees:

By this time there were groups getting breakfast, - not much but flour and water gruel with sometimes, a few greens gathered along the river. Those who had any possessions at all had a copper-kettle to cook in, and some had considerable quantities of bedding packed in the native trunks which are big woven cases. But there were many, oh so many, who had nothing, sleeping in the sun, sitting stupidly gazing about, hunting for and chewing mustard stems. A few bought pitiful bits of black bread from dirty peddlers squatted along the [railroad] track.

After two years in Erivan, Gertrude was assigned to manage the Boy’s orphanage at the NER station in Marsovan, Turkey, in June, 1921. Her arrival tragically coincided with a large-scale massacre and deportation of Greeks and Armenians in Turkish nationalist held territory. Gertrude, bearing witness to the events, provided relief to many of the victims.

Image Left: Gertrude Anthony, c. 1919.

When she left Marsovan for Constantinople in October of that year, she submitted a report to the American High Commissioner Admiral Mark Lambert Bristol. She emphasized in the report that it included only details as she knew “first hand, and such others” as she “felt reasonably certain were correctly told to” her. Aware of Admiral Bristol’s pro-Turkish nationalist sympathies, Gertrude feared that he would not pass her report onto the US State Department. To make certain they would receive it, she personally submitted her report to the State Department in Washington on her way home in December, with her sister, during their leave of absence. A State Department note attached to the report confirmed her suspicions and stated that Admiral Bristol had “not transmitted” the report “to the Department”.

Gertrude and Amy returned to Turkey in March 1922, Amy resuming her former work with the Kooleli orphanage. Gertrude, along with two other NER workers, Miss Charlotte Willard (Chicago, Ill) and Miss Panny G Noyes (Oberlin, Ohio), was assigned to return to Marsovan to relieve NER personnel Mrs C. Compton (Boston, Mass) and Miss Sara Corning (Hanover, N.H) who were leaving for vacation. The three women reached Marsovan in June and Gertrude resumed work at the Boy’s orphanage which housed about 600 orphans. Miss Willard took over as director of relief work and the premises owned by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) and Anatolia College. Noyes took charge of the hospital and the Girl’s orphanage. They were the only three Americans there.

Panoramic View of Constantinople, date unknown.

After the Turkish nationalist (Kemalist) victory over the Greek Army in western Anatolia and the subsequent Smyrna Catastrophe in September, 1922, an ultimatum was announced by the nationalists that non-Muslims had one month to leave Turkish nationalist held territory otherwise their safety could not be guaranteed. The announcement caused panic among the surviving Christian Greeks and Armenians throughout Turkey.

Samsun, as the closest major port to Marsovan with a strong American naval presence, became a destination for thousands of terrified refugees from all over the northeastern regions of the country. NER headquarters sent Gertrude Anthony an order to evacuate Marsovan. She began the 3 day, 65 mile journey to Samsun with 500 refugees and orphans crowded into a caravan of 56 wagons. Two fast wagons went ahead with workers so that they could cook food and have it ready on their arrival at their destination.

After safely arriving in Samsun, Gertrude took charge of receiving convoys of refugees from the interior of the country. In her own words, she described the state that refugees arrived in:

…were in bad shape for the rains began and there was snow in the mountains. The ones from Sivas were especially bad for they had an eight day trip. There was lots of measles and small-pox and pneumonia …. Refugees were pouring in and mobbing the house and the orphanages in their attempt to get help.

The existing NER buildings in Samsun were unable to cope with the vast number of refugees pouring into the port city. The destitute children became so numerous that Gertrude recalled, “…we had select those that looked hungriest.” NER had enough clothing supplies for the first 300 children but after that, children had to wear “underclothes and a blanket until we could wash and mend the best of their own clothes. About 600 were taken in ….”.

Gertrude decided to go back to Marsovan to assist her NER colleagues there. On the way there she saw fleeing refugees that reminded her of the conditions in Armenia. The refugees were… “[b]arefoot, ragged, dirty with the dirt of weeks of deep muddy roads, won out with terror and fatigue and hunger, some of the them sobbing, some gibbering, some stoical , – facing a blinding sleet storm. One woman with rags that exposed the entire length of her body…”

Gertrude arrived to a similarly desperate scene at Marsovan. Miss Noyes and Miss Willard had been receiving orphans from the NER orphanage further south in the interior at Tokat, which housed about 2,000 children. As they arrived in batches of 150 to Marsovan enroute to Samsun, many brought with them “cases of smallpox, measles and developed pneumonia”. Their mortality rate was quite significant and Gertrude reported that many died on the way and at Marsovan.

Gertrude left Marsovan at the end of January 1923 once the majority of orphans had successfully evacuated from the region. She left for Greece to help NER efforts there to cope with the country’s absorption of some 1 million refugees and orphans from Turkey. Gertrude found that in Greece it was “still a bitter struggle for the refugees” to survive. Many she said “are finding places. Many are wrecks and can never recover.”

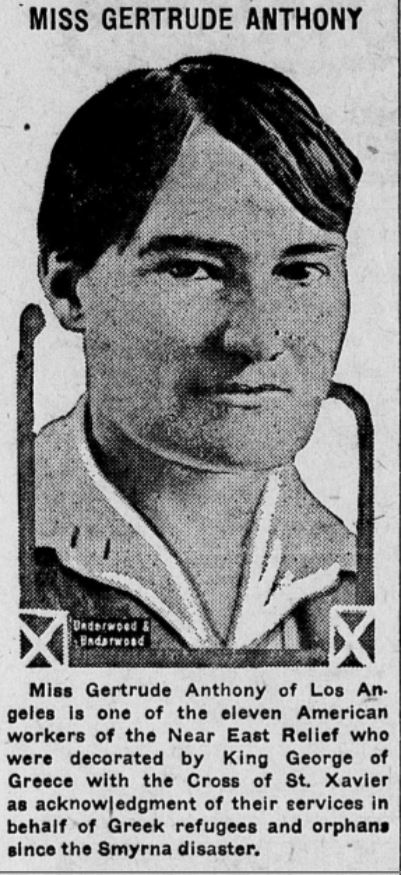

In late 1923, Gertrude, with eleven others, was awarded by King George of Greece with its highest civilian honor, the Golden Cross of Saint Xavier as “acknowledgement for their services in behalf of Greek refugees and orphans since the Smyrna disaster.” Gertrude continued to work in Greece and became the director of the Oropos orphanage which focused on Agricultural school work.

Gertrude Anthony, c. 1923.

The stories of the work done by Gertrude and Amy Anthony are emblematic of the progress made by women in the early 20th century. In the wake of such tragedies as the Armenian, Assyrian and Anatolian Greek Genocides, the need for citizen-based philanthropy and relief was so great that many women were able to take on leadership roles in a time when, despite great strides being made every day in women’s liberation and suffrage, women were still greatly limited in access and opportunities. As doctors, nurses, teachers, orphanage directors, relief coordinators, and many others, women like Gertrude and Amy Anthony represented the best of the ideals of the women’s movement and offered promise for the great progress that was still to come for all women, regardless of race, religion, or national origin, in the future.

References:

Vicken Babkenian and Peter Stanley, Armenia, Australia and the Great War (NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2016

Vicken Babkenian. “Humanitarian Responses to the Armenian Massacres 1894-1896”, International Review of Armenian Studies, Vol 16, No. 1, 2018.

Robert Shenk, America’s Black Sea Fleet: The US Navy Amidst War and Revolution, 1919–1923, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012

Gertrude Anthony papers, BANC MSS 2002/207, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Special thanks to Noushig Karpanian for providing material from the archive.

Near East Relief (newsletter), Edited by Near East Relief for private circulation, Constantinople, Volumes for years 1921-22.

Women Relief Workers Aboard the Leviathan, c. 1919.