Home, Hearth, & Family: The Rodosto Farm Colony

Five thousand refugees. Six thousand acres of farmland. At last, they had a place to call home. But for how long?

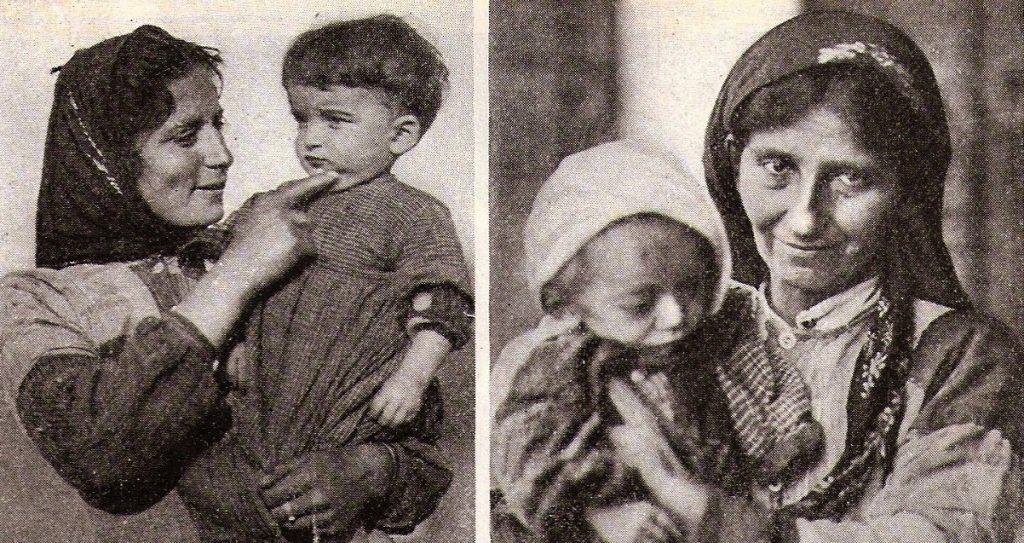

Many of the 6,400 refugees at Rodosto were women with very young children. 1922.

Curator’s note: When these events began, Rodosto was in Eastern Thrace, which was the easternmost part of Greece. Eastern Thrace is now the westernmost part of Turkey. The city is known by its Turkish name, Tekirdağ.

Rodosto, 1921. Near East Relief worker Peter Prins gazed across a vast expanse of unused land. Once a prosperous center for trade and agriculture, Eastern Thrace had been destroyed by the horrors of war. The residents had been driven from their homes in forced evacuations. Houses and farms fell into ruin. With no crops growing, the remaining villagers went hungry. Everywhere he looked, Prins saw desolation. But he also saw opportunity.

This rich land, so uniquely suited to crops like olives, wheat, and tobacco, could bloom once again. All Rodosto needed was people to till the soil. And Prins knew just where to find them.

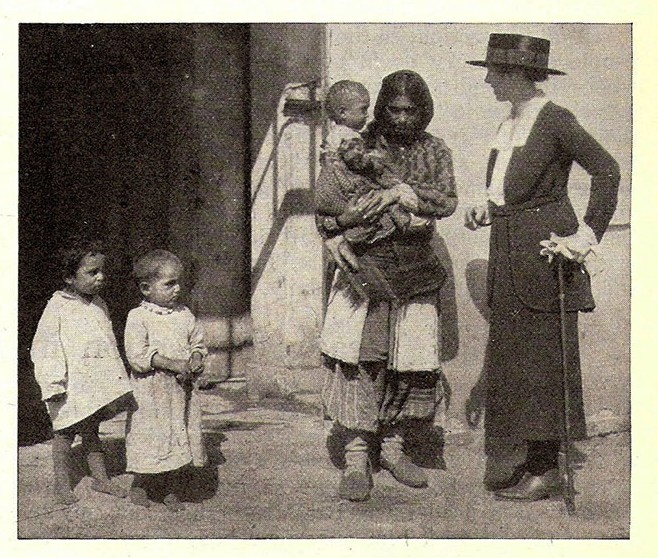

A Near East Relief worker watches as a refugee woman and man build a structure at Rodosto. 1922.

SEARCHING FOR A HOME

By the summer of 1921, Constantinople was overrun with refugees. Most of the refugees were Greeks and Armenians. Many had fled their homes in the wake of the retreating Greek and French armies.

They lived in makeshift camps and abandoned buildings. Sanitation was nonexistent, and disease was all too common. Food was scarce. An entire family might call a blanket-sized space in an old stable home.

The residents of Rodosto Farm Colony show off one of the many cottages that they built themselves. 1922.

Eighty-four miles west of Constantinople, 6,400 refugees had settled in Rodosto: roughly 3,600 Armenians, 2,600 Anatolian Greeks, 100 Turks, and 52 Jews. The refugees lived in four unused army barracks. Near East Relief provided soup and bread, and meat stew twice a week.

The food was prepared and distributed under the watchful eye of Near East Relief worker Margie Lin Caldwell. Near East Relief acquired a former blacksmith’s shop. Caldwell and her staff converted the old forge into a giant cooking stove. Refugee workers made pot after pot of soup from morning until night.

Children lined up with pots and bowls to collect their family’s small allotment of food. The Greek government was overwhelmed by a refugee crisis that would only get worse. The government contributed two cents per refugee per day, which made a small difference.

Margie Lin Caldwell visits with a refugee family, 1921.

LIVING WITH DIGNITY

The refugees were anxious to create new lives. There were few opportunities for tradesmen or farmers in desolate Rodosto. The men grew more and more frustrated with each passing day. That’s where Peter Prins stepped in. Prins negotiated with the Greek government and acquired 6,000 acres of land for Near East Relief’s use.

Prins envisioned a small farming community where refugees could have things that camp life could never offer: a house to live in, a plot of land to farm, a safe place to raise children. With these tools, a refugee family could live a simple but dignified life.

Most importantly, they would become self-supporting. The Armenian Central Committee agreed to pay the rent on the land. Near East Relief would provide farm equipment, seeds, and food until the farms became self-sufficient.

A caravan of Armenian refugees sets out for a new life at the Rodosto Farm Colony. 1921.

THE FIRST COLONISTS

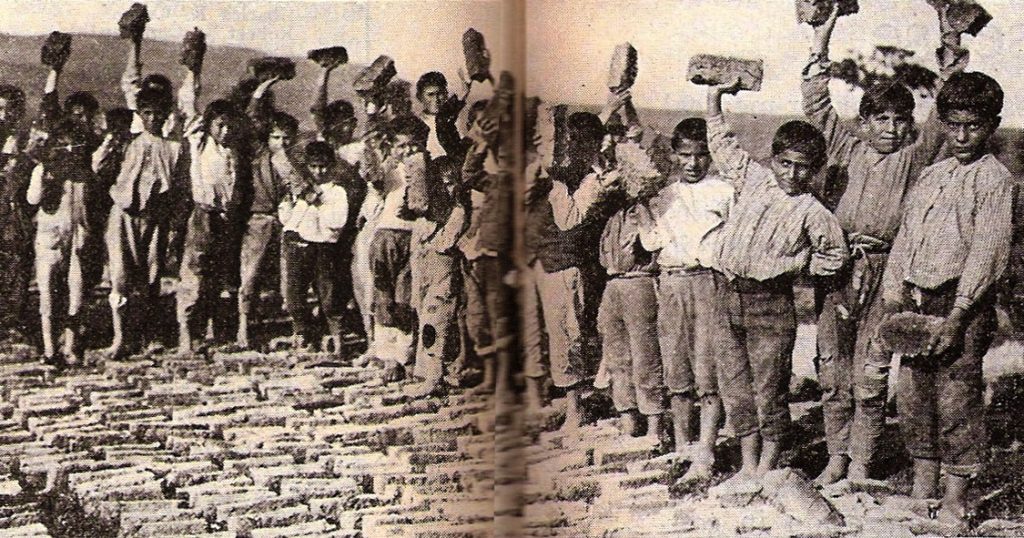

In the fall of 1921, 400 refugee men and boys left the barracks for the fields of Rodosto. Sturdy oxen pulled wagons laden with lumber, food, tools, and supplies. These were the first pioneers of the Rodosto Farm Colony. Their task was an ambitious one: the men and boys had committed to build houses for 100 families in time for the fall planting. They only had a few weeks.

When Peter Prins returned to the Farm Colony, he was astonished. Where he once saw abandoned land and crumbling buildings, he now saw a village of clay cottages, each with a red tile roof and a clay fireplace. In front of each cottage lay a pile of firewood.

The 400 men had already begun cultivating the farmland. Near East Relief provided seeds so the men could plant wheat and beans. Soon, their wives and children joined them at Rodosto.

A hardworking Rodosto farmer with his team of oxen, c. 1922. Near East Relief used this image on a promotional postcard.

The Rodosto Farm Colony grew quickly. In October 1921, Near East Relief workers Caris E. Mills and George Dennis sailed from Constantinople with 300 Armenian refugees — mostly families with small children.

The refugees were hesitant to travel to yet another camp. Many of them had been without a true home for years. They boarded the ship, carrying all of their belonging in bundles and baskets. The refugees ate a simple dinner of bread, cheese, and olives, and enjoyed a special treat of watermelon for dessert.

The families spent the night on the ship’s deck under thick Near East Relief blankets. They awoke in Rodosto. The families trooped to the nearby barracks at dawn. Three days later, they boarded trucks bound for the Rodosto Farm Colony.

This photograph of Rodosto boys making bricks was in the New Near East magazine in Sept. 1922. The magazine went to press just before the Smyrna Disaster.

MAKING RODOSTO BLOOM

Rodosto must have seemed like a dream. Each family was given a cottage. They immediately set out turning the houses into homes — their first homes in many years.

The farm colony was a hive of activity. Both men and women worked hard to make the settlement a reality. Men tilled and planted. Women made bricks and built walls. The goal was to resettle all of the refugees from the barracks into cottages before the long, cold winter set in.

Some of the refugees were hesitant to resettle in Rodosto. Former city dwellers were unsure about embarking on a new life as farmers. However, the opportunity for a private home was impossible to pass up. Carpenters quickly found work as builders. A few refugee teachers created a school. A baker opened a small but thriving bakery. The colony grew to include two villages.

In the spring of 1922, the villagers celebrated a momentous occasion: the once-barren fields were covered in small, sturdy shoots of wheat. They would soon harvest their first crops.

The Rodosto settlers were no longer refugees. They were farmers.

Right: Women tilling the soil at Rodosto, c. 1921. Library of Congress.

A boy with the first wheat harvest at Rodosto Farm Colony, 1922.

REFUGEES ONCE AGAIN

The September 1922 issue of The New Near East magazine featured a spread on the success of the Rodosto Farm Colony. Several of the pictures in this Dispatch are from that spread. By the time the magazine reached its subscribers, life in Rodosto had taken a dramatic turn. On September 13, 1922, fires swept through the culturally diverse port city of Smyrna. When the smoke cleared, the Greek and Armenian quarters had been looted and destroyed, and the city was under the control of the Turkish Nationalists.

The full impact of the Smyrna Disaster soon hit Rodosto. A new wave of refugees from Turkey descended upon Constantinople and Eastern Thrace, desperately searching for food and shelter.

In 1923, the governments of Greece and Turkey reached a startling agreement: they would exchange minority populations. Roughly 500,000 ethnic Turks were transported from Greece to Turkey, and roughly 1.5 million Anatolian Greeks were transported from Turkey to Greece. As part of the agreement Greece ceded Eastern Thrace to Turkey. The Greek and Armenian populations were forced to leave Rodosto.

The people of the Rodosto Farm Colony had worked so hard to create permanent homes. Yet after a few short years, they were refugees once again. They joined the tens of thousands of people on the road to Greece. Near East Relief redoubled its efforts to house families and orphans in places such as Salonika, Kavala, Athens, and Corfu.

To its proud residents, the Rodosto Farm Colony truly must have seemed like a dream — especially when it ended.

Left: Refugee woman on the deck of a ship. Three children are tucked under a blanket. Date and location unknown.

Postcard from Rodosto. Image courtesy of the Levantine Heritage Foundation.

Special thanks to the Levantine Heritage Foundation and the Asia Minor and Pontos Hellenic Research Center.