Constantinople, Part 3: Saving Lives at Selimieh

Life in Constantinople in 1922 was profoundly difficult, and it would get worse before it got better.

This is the third in a series of Dispatches on Near East Relief’s work in Constantinople. You can read parts 1 and 2 here and here. Special thanks to NERHS intern Casey Edgarian, who contributed research on this Dispatch.

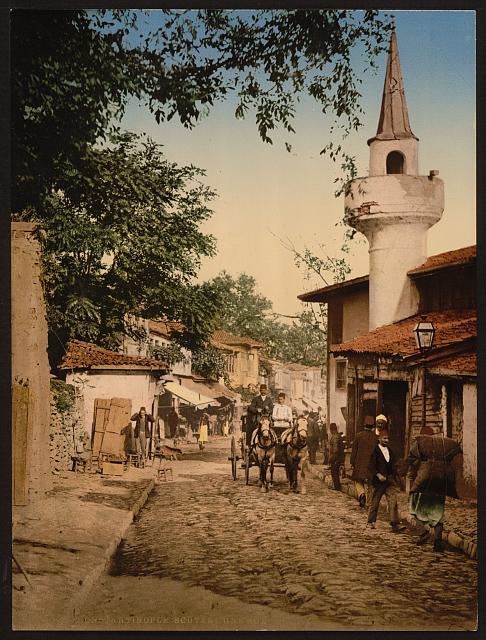

Photochrom image of a street in Scutari, Constantinople [now Üsküdar, Istanbul], c. 1890-1900. Library of Congress.

ON THE BANKS OF THE BOSPHORUS

Scutari, Constantinople: 1923. Relief worker Christopher Thurber has just arrived in Constantinople from Sivas, a small city in the Turkish interior. He hasn’t come alone. Thurber has made the 550-mile trip with 7,000 Near East Relief orphans.

Thurber is still weak from the bout with typhus that nearly took his life at the Sivas Orphanage. Nonetheless, he is ready to embark on his next assignment as a Near East Relief worker. He stands before an imposing white building that takes up an entire city block on the Asian side of the Bosphorus. Thurber is preparing to make his daily rounds at the Selimieh barracks — a former military facility that is now home to more than 9,000 refugees.

Right: Photochrom image of a street in Scutari, Constantinople [now Üsküdar, Istanbul], c. 1890-1900. Library of Congress.

View of the Selimieh barracks, which housed more than 9,000 refugees, c.1922. From The Story of Near East Relief by Dr. James L. Barton.

FROM ARMY BARRACKS TO REFUGEE CAMP

How did a massive Ottoman army barracks become home to more than 9,000 refugees fleeing military violence? The original Selimieh (or Selimiye) barracks were built in Scutari, Constantinople to house Ottoman janissaries in 1800. The first building was designed by prominent Armenian architect Krikor Balyan. It was made of wood.

The barracks burned to the ground during a military revolt in 1806. They were rebuilt, this time from stone, in the 1820s. The new complex was made up of four connected buildings that formed a square around an interior courtyard. The barracks were designed to hold 3,000 Ottoman soldiers.

The Selimieh barracks gained international attention during the Crimean War, when British troops were quartered in the huge building. Englishwoman Florence Nightingale famously nursed British soldiers back to health there. In fact, Nightingale is credited with inventing the modern nursing profession at the Selimieh barracks.

Map showing the distribution of ethnic groups in Constantinople. From Constantinople To-Day, 1921.

AN INFLUX OF REFUGEES

By 1922, Constantinople was hosting more than 100,000 refugees of various ethnicities. While the Allied forces worked in Constantinople alongside the Ottoman government, former Ottoman military officer Mustafa Kemal had assembled a competing Turkish Nationalist government in Ankara. The Nationalist army waged a war of Turkish independence, targeting minority groups throughout the country.

The destruction of the multicultural city of Smyrna in September 1922 set off a new wave of refugees that would change the face of Constantinople yet again.

Christopher Thurber and his orphans were not the only people to leave the Turkish interior in the wake of the Smyrna Disaster. Tens of thousands of ethnic Greeks fled southwest Turkey and the Black Sea coast in an effort to escape the advancing Turkish Nationalist army. The Selimieh barracks housed a small portion of the 25,000 Greek refugees that arrived in Constantinople. Thousands of refugees were stuck on ships in the harbor for months. There was simply no place for them to go on land.

Constantinople is menaced by the worst epidemic of diseases in its tragic history. . . Many of those who survived their march of terror to the sea died on shipboard and 60% of those who lived through the voyage of filthy, crowded ships, were diseased on arrival here.

FIGHTING DISEASE

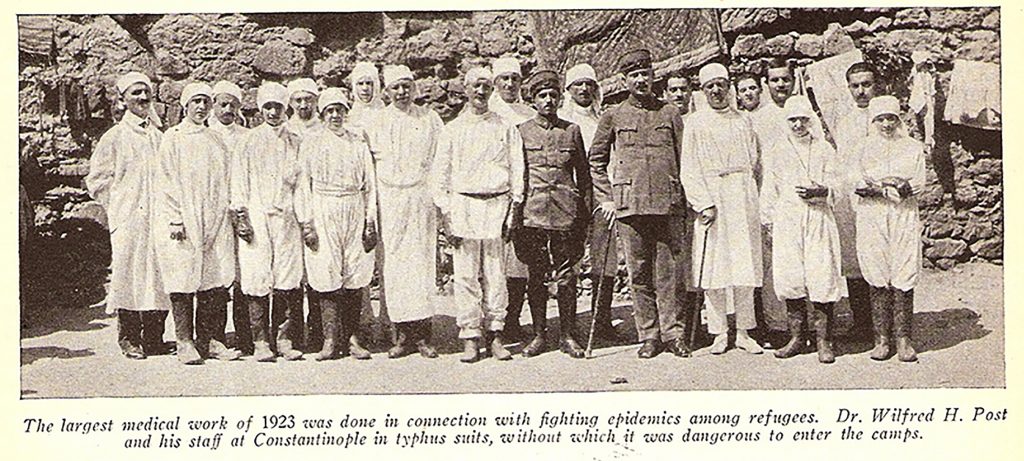

Christopher Thurber was not alone in his work at Selimieh barracks. Thurber worked alongside Dr. Wilfred Post, an American Red Cross physician on loan to Near East Relief. Dr. Post had directed the Near East Relief hospital at Konia (Konya) until that station was evacuated. Post and Thurber led a team of Armenian and Greek doctors and nurses, as well as American Near East Relief workers.

Every day, Thurber and Post made the rounds of the refugee communities in Constantinople. They visited Selimieh, where Greek refugees to survive from one day to the next. Dr. Post reported that here were more than 9,000 refugees living in a building meant to hold 3,000 soldiers.

As in many refugee camps, the unsanitary conditions created a breeding ground for disease. A typhus epidemic swept through the Selimieh barracks in 1923. The death rate in the crowded camp rose to an astonishing 140 people per day.

Near East Relief estimated that 500 refugees — women, children, and the elderly — were dying in Constantinople every single day.

Left: Thurber and Post in “bug-proof” suits. Dr. Post created these suits to protect medical workers from disease in refugee camps.

The Greek and Armenian refugees in Constantinople probably number 30,000. The Armenians have been here for a long time and are tolerably well taken care of, but the plight of the 25,000 Greeks is becoming daily more pitiable.

The building with the peaked rooftops is a Near East Relief supply warehouse. Constantinople, 1922. Library of Congress.

Near East Relief worked with other aid organizations in Constantinople to address this new humanitarian disaster. Aid workers created a bakery and bread station inside the Selimieh barracks. Families received soup based on the number of family members. On a good day the soup contained rice, potatoes, and a sprinkling of olive oil. The refugees slept on mats; the most fortunate also had blankets. One thousand refugees lived in the former stables.

In addition to food, the refugees received health care and sanitation lessons. The relief workers promoted sanitation at Selimieh with an effective, if harsh, system: any person who broke the rules did not receive bread for the day.

Dr. Post and his staff created isolation wards to slow the spread of disease. By October 1923, the death rate at the Selimieh barracks had dropped from more than 100 people per day to 25.

The loss of life was not limited to the refugee community. Ten Greek doctors died of typhus during the epidemic. Five Near East Relief workers contracted the disease while caring for refugees at Selimieh. Henry Flint succumbed to typhus.

CROSSING THE AEGEAN SEA

In 1923, Greece and Turkey agreed to a tumultuous population exchange. Near East Relief and the American Red Cross began the slow process of transferring ethnic Greeks from Turkey and resettling ethnic Turks arriving from Greece. The population exchange did not just apply to the Greeks in Constantinople — every Greek would have to leave Anatolia. Near East Relief chartered tugboats full of food and medical supplies to meet incoming and outgoing refugee ships.

The population exchange lasted for several years. By 1925, roughly 1.3 million ethnic Greeks had sailed across the Aegean from Turkey to Greece. Approximately 500,000 ethnic Turks had been transported from Greece to Turkey.

WHAT ABOUT THE ORPHANS?

So far, this series of Dispatches has focused on adult refugees and their families in Constantinople. Near East Relief’s work with refugees was secondary to its main purpose: the countless children left orphaned by violence and disease. Near East Relief workers faced a painfully simple question.

How could Near East Relief save the lives of tens of thousands of orphans in Constantinople?

Check back soon for our next Dispatch.