On the Road With Annie T. Allen: Part 2

When we left off with Near East Relief worker Annie T. Allen, she and her fellow travelers had just arrived at a Turkish Han for a restful evening. Let’s catch up with Annie in this, the second installment of her diary from a September 1920 trip through Anatolia. You can read the first installment here.

A Near East Relief vehicle travels through the dusty desert. Possibly Persia, c. 1920.

Curator's Note

When Miss Caris E. Mills, the editor of the Near East Relief, heard that veteran relief worker Annie Allen was planning a trip to the Turkish interior, she asked Allen to keep a diary for the newsletter. The following diary entries were published in the April 9, 1921 issue of Near East Relief.

Sadly, the original article does not include any photographs. We have added images that we think are in keeping with the spirit of Annie Allen’s words.

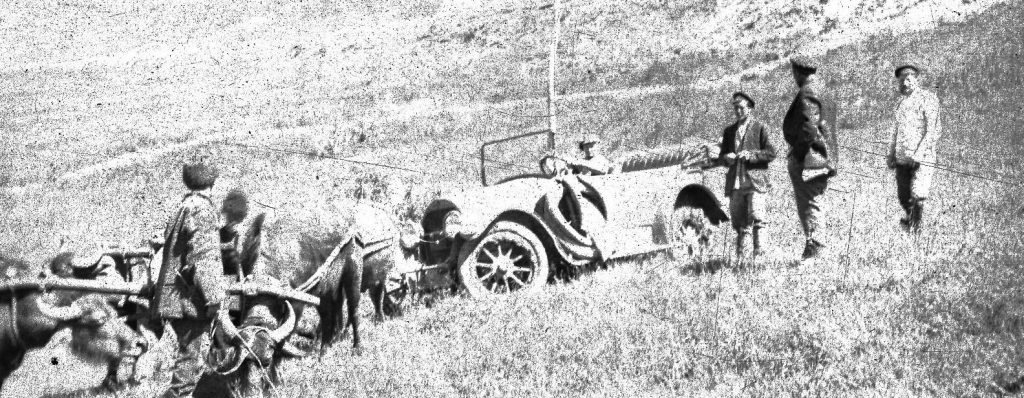

Unidentified Near East Relief workers traveling by car take a break from their journey. Date and place unknown, 1920s.

September 11th, 1920

Do you believe in the evil eye? Well I do today. Certainly some one has cast an evil eye on our auto and we have no blue bead on it. Going up a steep incline in the narrowest part of the road, the car suddenly stopped and I was told we had a broken differentiator.

The truck was ahead of us, going very slowly, so Tahsin [the driver] rushed after it and succeeded in stopping it. We decided to transfer all our light luggage to the truck and then climb on ourselves. During the process of transfer we saw two caravans approaching from either direction.

One was made up of wagons and the other buffalo carts. After many shouts and maneuvers, they passed our two automobiles and the coast was clear.

Traveling by automobile in the Near East was challenging, and sometimes even dangerous. Probably the Caucasus, c. 1920.

While waiting by the roadside, I fell into conversation with two Turkish women who were with the buffalo train. The older woman said to me, “look at my grey hairs and see how I am toiling along barefooted in this dust and you are sitting there like a lady, clothed from head to foot — even your hands are covered.”

I told her we too were having our troubles of another kind and that we were taking this rather difficult journey to carry relief to orphans and refugees. Whereupon she said, “I have two orphans for whom I must care.” [Fatherless children were often called orphans].

I was sorry I did not have a little money handy to give the poor soul. These poor Turkish peasant women, because their husbands are soldiers, must toil thus, walking sometimes five and six days to the coast so as to feed and clothe their children while the husband is away.

Is it possible that some say we should not help these people? That is not the Christ spirit.

Right: Six refugee children, probably Armenia, c. 1920.

Near East Relief workers used every possible mode of transportation, including cars, horses, and camels. Possibly Persia, c. 1920.

September 25th, 1920

My diary has gone untouched for many days. The story for each day is about the same — dust, auto breakdowns, Turkish Hans, with a few Near East Relief stations which were like oases in the desert.

At these stations we were warmly welcomed and royally treated, our only regret being that our need for hurried transit gave us but little time to see the good work which was being don in all these places.

We had no exciting adventures along the road. The nearest we came to real excitement was going through a pass where a day or two before several hundred brigands had made a raid on a village Han and had also attacked many wagons. Six or seven of the villagers were said to have been killed. The Han, which we found empty, and the many vultures feeding on the prey in a field beyond, testified at least that the statements of the villagers were not far from the truth.

After we had travelled through the most dangerous part of the pass, our auto broke down. We sat down by the roadside while it was being repaired. Soon some villagers came along and I asked how the road was. One looked at me for a minute and then said, “What are you?” When I told him we were Americans, he said “The road is safe for you. We would pluck out our eyes for you.”

Left: Refugee women and children waiting for work in Marsovan (now Merzifon), c. 1918. Library of Congress.

The Turkish Nationalist Parliament building in Angora (now Ankara), c. 1922. Annie Allen met with Mustafa Kemal in Angora.

We two American ladies traveled from Marsovan to Cesarea with no companions save our two Turkish chauffeurs, a trip of five days. We had no fear and we were pleased to have proved that American ladies could travel alone unharmed through the interior of Turkey.

We reached here, Konia, at midnight, and found Miss Cushman and Miss Gaylord waiting up for us, and glad they were for word from the outside world. Miss Cushman is soon to leave us for her much needed rest while I remain here until Dr. Dodd comes to take charge of the work here in Konia.

This concludes Annie T. Allen’s diary as published in the Near East Relief newsletter.

View of Broussa, where Annie T. Allen served as a missionary and relief worker. Library of Congress, c. 1890.

Remembering a Heroic Woman

Annie Theresa Allen was born to missionary parents in Harpoot, Turkey, in 1868. She attended high school and college in the United States, graduating from Mount Holyoke College in 1890. Allen returned to Harpoot after graduation and spent some time in Van. In 1903 she accepted a full appointment from the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions. She served in Broussa from 1903 to 1909, when her health forced her to return to the U.S.

Allen returned to Broussa in 1912, as soon as she was well enough to resume her work at Broussa Girls School. Allen stayed in Turkey through World War I. She refused the offer of furlough from the ABCFM when the war ended, and elected to join Near East Relief. Allen was fluent in English, Turkish, and Armenian; she thought of Turkey as her home. She felt a deep personal connection to both the Armenians and the Turks.

In 1921, Near East Relief asked Annie Allen to serve as the director of the Angora (now Ankara) station. She was the only American in Angora during the earliest days of the Turkish Nationalist movement. Annie Allen became an unofficial liaison between the Mustafa Kemal’s government, Near East Relief, and the Allied Powers — she was essentially an American diplomat in a place with no diplomatic ties to America.

Allen had two crucial meetings with Mustafa Kemal and his chief of staff in April 1921. She secured a guarantee of safety for Americans living under Nationalist control, as well as the all-important right for American relief workers to travel within Turkey. Were it not for Allen’s shrewd negotiating, Near East Relief could not have continued its work in Turkey; this agreement ultimately allowed Near East Relief workers to safely evacuate thousands of orphans from the Turkish interior.

Annie Allen travelled frequently. In January 1922, she embarked on a trip from Angora to the Near East Relief station in Sivas. Just before she reached her destination, Allen fell from her carriage and sustained serious injuries. The examining physician discovered that Allen was also gravely ill with typhus. Annie T. Allen died in Sivas on February 2, 1922. She was buried with full Turkish Nationalist military honors, including a guard of honor. Turkish government officials attended the funeral.

Today, this heroic, intelligent woman has been largely forgotten. Let us remember Annie Allen and celebrate her incredible legacy.

Left: Annie T. Allen’s graduation portrait, 1890. Courtesy of the Mount Holyoke College Archives.

Postcard of Samsoun (Samsun), c. 1909. Public domain image.