The Armenian, Assyrian, and Anatolian Greek Genocide: Facts & Fundamentals

This is the first in a series of Dispatches on the Armenian Genocide.

Armenian refugees leaving Turkey, c. 1920.

Difficult Questions

If you are reading this, you are probably already familiar with the Armenian Genocide and Near East Relief’s response. This April 24, countless people will learn about it for the first time when the world marks the 101st anniversary.

I (Molly, your curator) first learned about the Armenian Genocide on a museum visit in my early 20s. Or to put it differently, I went through high school, college, and most of graduate school without ever learning about the Genocide. My first question was “why did this happen?” My second was “why didn’t I know about this?”

As April 24 approaches, NERHS has decided to address some fundamental questions to help more people learn about this important history. As with all good historical questions, there are short answers and long answers. These are the short answers. You will find much more information in our Exhibit.

What Was the Armenian Genocide?

The Armenian Genocide took place in 1915 in the Ottoman Empire, when the Ottoman military targeted ethnic Armenians living in the empire with deportations and massacres. An estimated 1.5 million Armenian men, women, and children were killed.

The Genocide was not so much a single incident as a long series of events. Armenians faced discrimination and violence long before 1915, and the massacres continued for several years while the political climate changed. Many scholars consider the Genocide to have taken place from 1915 to 1923. For the purposes of this exploration, we will be looking at the events of 1915.

The Ottoman government and the subsequent regime also targeted other minority groups, including Ottoman Greeks and Assyrians. Some historians consider the groups separately, while others refer to these events collectively as the Armenian, Anatolian Greek, and Assyrian Genocide.

Left: studio portrait of Muslim, Kurdish, and Armenian women from Sivas province in traditional costumes, c. 1873. Library of Congress.

Who Were the Ottoman Armenians?

By the time the Ottoman Empire was formed, the Armenians had been living in Anatolia and the Caucasus for more than 3,000 years. An empire is a combination of different ethnic peoples and territories ruled by a central power. Empires are by definition multicultural, with multiple languages and diverse religious practices. But not everyone is treated equally.

The Armenians were just one of many minority groups that lived as dhimmi — non-Muslim subjects with limited rights — in the Ottoman Empire. Dhimmi were permitted to worship but were denied the rights of full citizenship.

The Ottoman Armenians had a long history as a Christian culture. Armenia adopted Christianity as its official religion in the 4th century. Many young Ottoman Armenians attended mission schools run by American and European missionaries.

As a result of the foreign missionary influence, some Ottoman Armenians were Protestant or Roman Catholic, and many spoke several languages. The Armenians’ religion set them apart from the Ottoman Turks, who were Muslim. Scholars estimate that there were 2 million Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire when World War I began in 1914.

Right: studio portrait of an Armenian priest, Turkish mullah, and Greek priest from Konia province, c. 1873. Library of Congress.

Why Did the Genocide Happen?

The Christian missionary school system had produced an educated class of Armenians that began to advocate for the civil and political rights that had always been denied to them. At the same time the Ottoman Empire was collapsing. More and more territories were declaring independence, and years of war with Russia had drained the Empire’s resources.

This highly charged political atmosphere gave rise to an opposition group called the Young Turks, which opposed the Sultan and sought a constitutional government. The Young Turks joined forces with the revolutionary Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). The new government adopted a policy of Turkification: the forced transition from the multicultural Ottoman Empire to a homogenous Turkish state.

The Armenians were not the only group that did not fit into this new policy. Ethnic Greeks, Assyrians, and other religious minorities living throughout the Ottoman Empire were targeted. Government propagandists argued that a strong society must have only one culture, one religion, and one level of education. CUP leaders portrayed non-Muslims as an invasive virus within the Turkish nation.

The Ottoman Empire had been fighting the Russian Empire for decades. When World War I began in 1914, it thrust the Ottoman Empire’s treatment of minority onto the international stage. Germany was an essential ally in the CUP’s ongoing struggle against the Russian Empire to the east.

The Ottoman army allied with the Central Powers. This alliance allowed the CUP to improve its military forces and technology. World War I created a suitably chaotic backdrop for the Ottoman Empire to target groups of its own people for extermination. Hundreds of years of persecution culminated in mass murders and deportations.

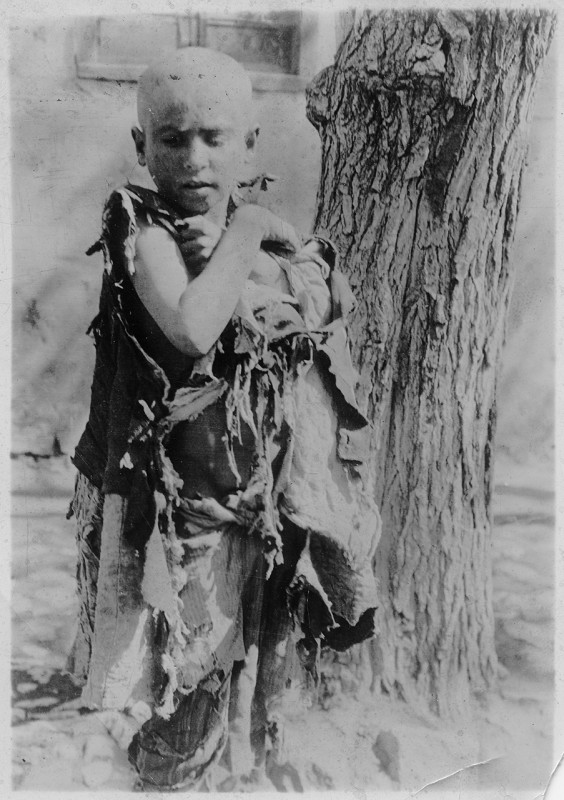

Left: an Armenian boy in rags, date and location unknown.

Deportation of and excesses against peaceful Armenians is increasing and from harrowing reports of eye witnesses it appears that a campaign of race extermination is in progress under a pretext of reprisal against rebellion.

What Happened During the Genocide?

When World War I began, Armenian men age twenty and older were drafted as laborers in the Ottoman military. They were forbidden to carry weapons. Defenseless and despised, many Armenian laborers were massacred in isolated areas.

The CUP also accused Armenians of collaborating with the Russian army. The Ottoman government used its failed invasion of Russia as a pretext to destroy the Armenian population.

The first deportations took place in the city of Zeitun on April 8, 1915. Men were marched out of town and executed. Women and children were loaded into railroad cars bound for the desert. The Zeitun deportations served as a training event for the Ottoman killing squads.

The CUP soon launched an attack on the Armenian intellectual community. On April 24, 1915, soldiers arrested approximately 250 Armenian cultural leaders in the diverse city of Constantinople. Within a few weeks the military had deported more than 2,300 men from northwestern Turkey.

Resistance became a pretext for massacre. Armenian men were taken from their villages and killed. The remaining women, children, and the elderly were not spared. Thousands were forced into cattle cars on the Baghdad Railway, headed for “resettlement” in Der el Zor. Others were made to march on foot. Most of the people who survived the death marches died of starvation and disease in the desert.

This concludes Part 1. Check back soon, or subscribe to receive an email when Part 2 is published.

(c) 2016 The Near East Foundation

Ottoman Turks stand over Armenian deportees from Zeitun. Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute.