Near East Relief in Aleppo

Between 1915 and 1925 the city of Aleppo, Syria welcomed tens of thousands of Armenian orphans and refugees. Aleppo became a thriving center of the Armenian diaspora.

A City of Refugees

In the ten-year period between 1915 and 1925, Aleppo accepted three massive waves of Armenian refugees. The first genocide survivors arrived in the wake of the deportations in 1915. The Ottoman government had sent hundreds of thousands of Armenians on death marches to Der-El-Zor, where they faced disastrous living conditions in the desert. Many survivors of the deportations fled on foot, bound for the safe haven of Aleppo. They settled in makeshift refugee camps, where they received food, clothing, and medical care from Near East Relief workers. The city earned a reputation as an accepting place to start a new life.

At left: Armenian woman kneeling beside dead child in field “within sight of help and safety at Aleppo,” according to the original caption. Library of Congress, Bain Collection.

Thousands of other survivors had tried to make their way home after the deportations. Many returned to the Cilicia region, where they attempted to revive the once-vibrant Armenian communities Marash, Adana, and other towns. Beginning in December 1918, Cilicia was under the control of the French government — and under the protection of the French military. After a long and devastating conflict with Mustafa Kemal’s Turkish Nationalist army, France ceded Cilicia to Turkey in October 1921. This launched a new wave of refugees bound for Syria. Thousands of Armenian genocide survivors fled Cilicia on the heels of the retreating French army.

View of Aleppo. Photo by University of Michigan Expedition, George R. Swain, Ann Arbor, MI. Courtesy of the Armenian General Benevolent Union, Ellen Mary Gerard Collection.

A Growing Armenian Community

Near East Relief began its work in Aleppo by providing financial support for existing institutions during World War I, when new aid workers could not enter Syria. The first Near East Relief workers traveled to Aleppo after the Armistice. A Near East Relief physician, Dr. Robert A. Lambert, was given the daunting task of assuming control of and expanding the American Red Cross’ wartime work in northern Syria. Dr. Lambert was named Medical Director for all of Near East Relief’s stations in northern Syria. As in many areas served by Near East Relief, typhus and trachoma were rampant.

Near East Relief assumed control of an existing orphanage in Aleppo. The old, overcrowded stone buildings housed an incomprehensible 1,600 children. By late 1921, Near East Relief had opened a second orphanage to meet the growing need for shelter. The new orphanage was more of a camp, albeit a scrupulously clean one. Eight hundred children lived in tents. They enjoyed comparatively ample space, including outdoor play areas, and followed a strict hygiene program. Dr. Lambert reported that trachoma rates hovered near 60% for both facilities, but the children in the camp recovered much more quickly, and there were fewer new cases.

By November 1921, Aleppo had seven general hospitals and one specialized eye hospital. At right: young boys in uniform on the steps of the Near East Relief orphanage in Aleppo, 1924. The photograph has been retouched by hand, which gives it a stylized appearance.

Near East Relief eye hospital in Aleppo, 1920. Photo by University of Michigan Expedition, George R. Swain, Ann Arbor, MI. Courtesy of the Armenian General Benevolent Union, Ellen Mary Gerard Collection.

Caring for New Arrivals

Many adult refugees found jobs with Near East Relief in Aleppo. Armenian health professionals became essential members of the Near East Relief medical staff, which catered to an ever-increasing refugee and orphan population. At left: Orphanage superintendent Rev. Shiradjian, Dr. N. Ishkanian, and Near East Relief nurse Ellen M. Norton, 1921. Mrs. Norton wears an armband with the Near East Relief star. Courtesy of the Armenian General Benevolent Union, Ellen Mary Gerard Collection.

The burning of Smyrna and the Greco-Turkish War brought yet another wave of refugees to Syria in late 1922. The influx included 12,000 children from Near East Relief orphanages in the Turkish interior. Life in the orphanages in Aleppo was simple, but friendly. Each child had a small mattress, which could be rolled up when the dormitory needed to serve as classroom or playroom. Each orphan received a small box for his or her personal belongings. Near East Relief workers encouraged recreational activities between the orphans and local children in an effort to encourage friendliness and goodwill between the communities.

The Near East Relief evacuation from the Turkish interior brought one very unique group to Aleppo. Near East Relief had operated the American School for the Blind in Harpoot. In 1922, one hundred blind children journeyed from Harpoot to Aleppo. The children, who ranged in age from seven to fifteen, walked through the desert and climbed bandit-infested mountains. They even floated on barges for twenty miles on the Euphrates River. The 500-mile journey took one month.

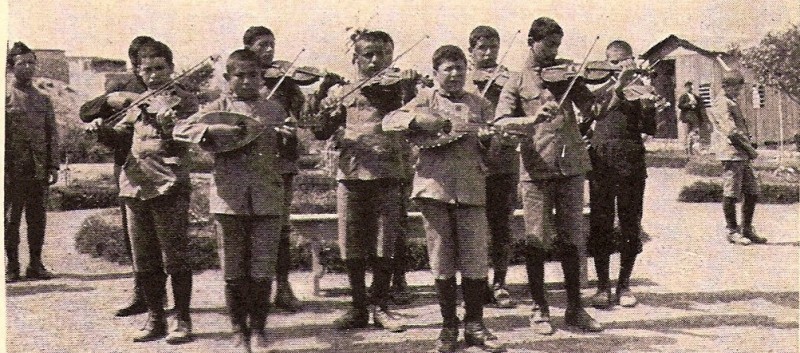

Near East Relief re-established the School for the Blind in Aleppo. The students learned to read Braille, and even made their own Braille cards to combat the lack of supplies. They received vocational training in weaving and sold handmade baskets and mats. They also formed an orchestra (right) that played for visitors and for patients at the orphanage hospital.

By 1923, Aleppo had received nearly 100,000 refugees: 79,000 Armenians, 8,000 Anatolian Greeks, and several thousand Near East Relief orphans evacuated from the Turkish interior.

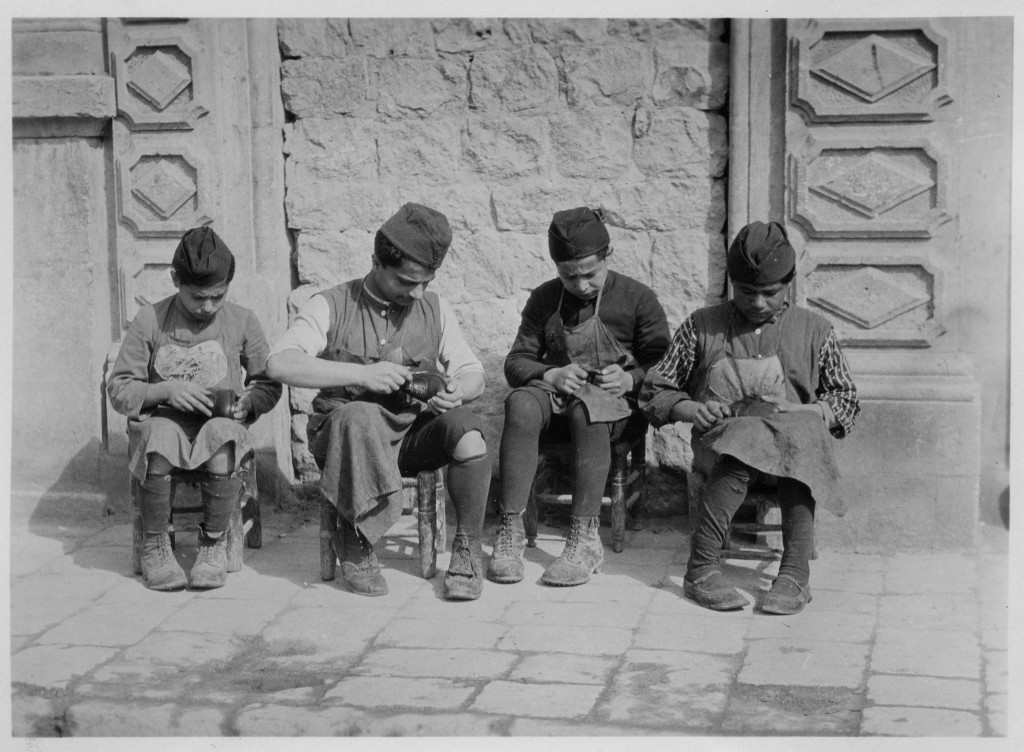

Near East Relief orphans training as cobblers in Aleppo, c. 1923.

"The Street of Near East Relief"

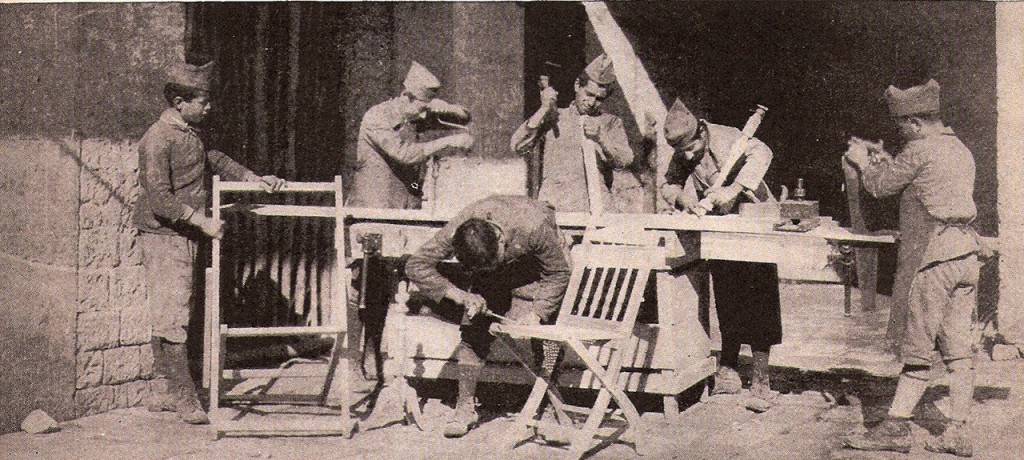

Armenian Near East Relief orphans in Aleppo received a primary school education in their native language. Some ambitious students studied English as well. By late 1922, Aleppo boasted a new shopping area known as “the Street of Near East Relief.” Each shop focused on a specific Near East Relief trade, and was staffed by orphans learning that trade. Visitors to the area — tourists and locals alike — commented on the quality and variety of goods on offer. Teenage boys training to be tailors offered made-to-order garments and alteration services at the Near East Relief clothing store (right). Young cobblers turned out boots and shoes modeled after American styles, while tinsmiths and silversmiths produced traditional ornaments. The street also featured upholsters and cabinetmakers.

While female orphans were generally less involved in public trades, the girls of Aleppo struck up a lucrative textile business. Handmade lace and fancy needlework were popular with shoppers from all backgrounds in the diverse city. In 1922, needlework sales commanded a profit of $250 per month on the Street of Near East Relief!

More than 900 boys worked as apprentices on the Street of Near East Relief. Five Armenian adults served as supervisors. The boys received wages for their work. One quarter was given to the boy outright, one quarter was given back to the orphanage in exchange for room and board, and the remainder was placed in a bank account in the boy’s name. The boys received this nest egg when they graduated at age 16. Many used the money to start their own businesses.

Aleppo was home to a thriving chapter of the Near East League, Near East Relief’s alumni association for orphanage graduates. The League held meetings on Sundays and hosted social events at least once a month. Members were encouraged to take classes through the League and participate in sporting events. Near East League members also helped one another to find jobs and housing.

The history of relief work in Aleppo is as complex as it is fascinating. Individuals like Karen Jeppe, Jacob Kunzler, and Ellen M. Norton deserve their own Dispatches (and will hopefully receive them soon).

Young Near East Relief carpenters in Aleppo, 1924.

One Hundred Years Later

One cannot read or watch the news today without hearing about the Syrian refugee crisis. Aleppo — that thriving city that once opened its doors to thousands of Armenian refugees — is now a war zone, its people driven from their homes by the greatest migrant crisis of our time. Before the conflict began five years ago, an estimated 100,000 ethnic Armenians lived in Syria; almost 60,000 lived in Aleppo. The vast majority were descendants of survivors of the Armenian genocide.

As of September of this year, an estimated 15,500 Syrian Armenians have sought asylum in Armenia. More than 1.5 million Syrian refugees (including Syrian Armenians) have traveled to Lebanon. Armenian families have flooded Bourj Hammoud, an area northeast of Beirut with a long Armenian history. Today, the streets of Bourj Hammoud bear an uncanny resemblance to images from the early 1920s, when Armenian genocide survivors first formed a refugee settlement on the swampy banks of the Beirut River.

One hundred years later, the connections between our origins as Near East Relief and our current work as the Near East Foundation are clearer than ever.

Learn More About NEF's Current Work With Refugees

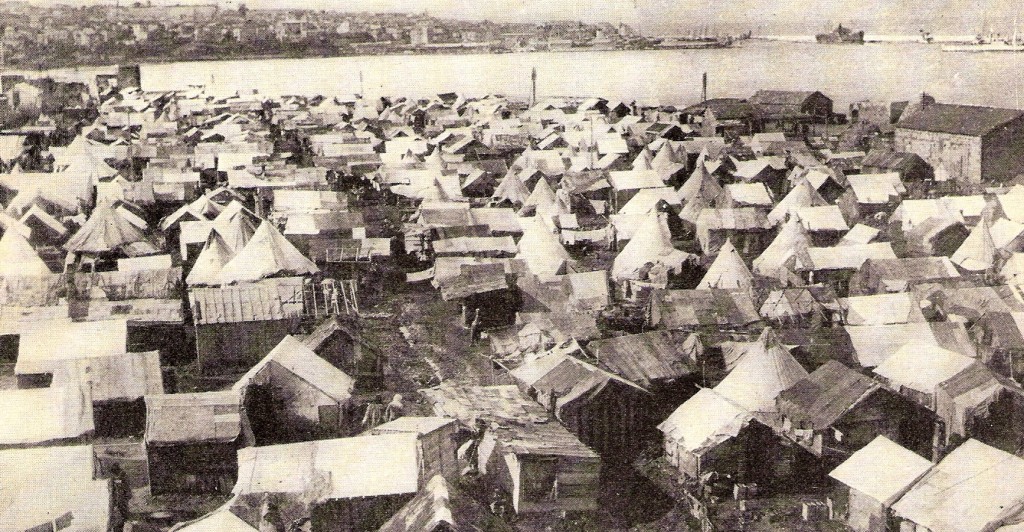

A tent city in Beirut, 1923. The original caption states that this area was home to 6,000 Armenian refugees. Aleppo was home to 79,000.