Every Stitch a Story: Near East Industries

Near East Industries provided a source of income for thousands of refugee women. It was much more than a series of shops — it was a means of cultural preservation.

From the beginning, Near East Relief sought to provide children with marketable skills and adult refugees with an opportunity to earn a living. Near East Industries developed naturally from the textile workshops created by pioneering relief workers like Constance Sheltman. Visitors to Near East Relief centers consistently praised the beauty and uniqueness of the women’s wares, particularly the traditional weaving and embroidery which were so exotic to the American eye.

The organization’s leaders saw an opportunity in these ornate items. But who could turn a few small handcrafts workshops into a successful export company? Two Near East Relief workers held the answer.

From Relief to Entrepreneurship

Priscilla Capps Hill was practically born to a career in the Near East. Her father, Princeton University professor Edward Capps, was a noted classicist and the former U.S. Minister to Greece. She joined Near East Relief in Athens in 1923 and was named overseas director of Near East Industries in 1925.

Rose Ewald (right) of Yonkers, NY, had spent six years as a Near East Relief worker in various locations. She had been the supervisor of supplies at the Kazachi Post factory, insuring that the workers had the raw materials to sew clothing for 15,000 orphans.

Ewald traveled to other Near East Relief centers in Turkey and Syria. She saw women and girls producing beautiful garments, lavish carpets, and delicious preserves to sell in the community. These goods were popular souvenirs for American tourists to the Holy Land. Ewald was particularly impressed by the weaving and embroidery produced by refugee women in Greece and Syria.

When Ewald returned to the U.S., she agreed to serve as the American director of Near East Industries — a Near East Relief subsidiary dedicated to employing refugee women and selling their handcrafts.

Preserving Tradition

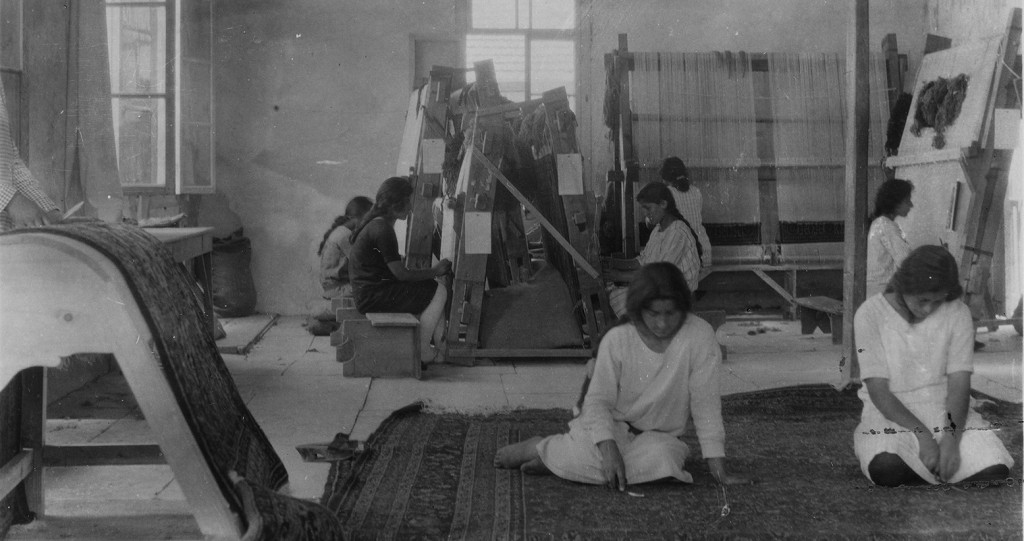

Near East Industries employed women exclusively. Most of the workers in Greece had arrived in that country as refugees after the Smyrna disaster in 1922 or the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923. On average, each woman had four dependents and was the sole breadwinner for her family.

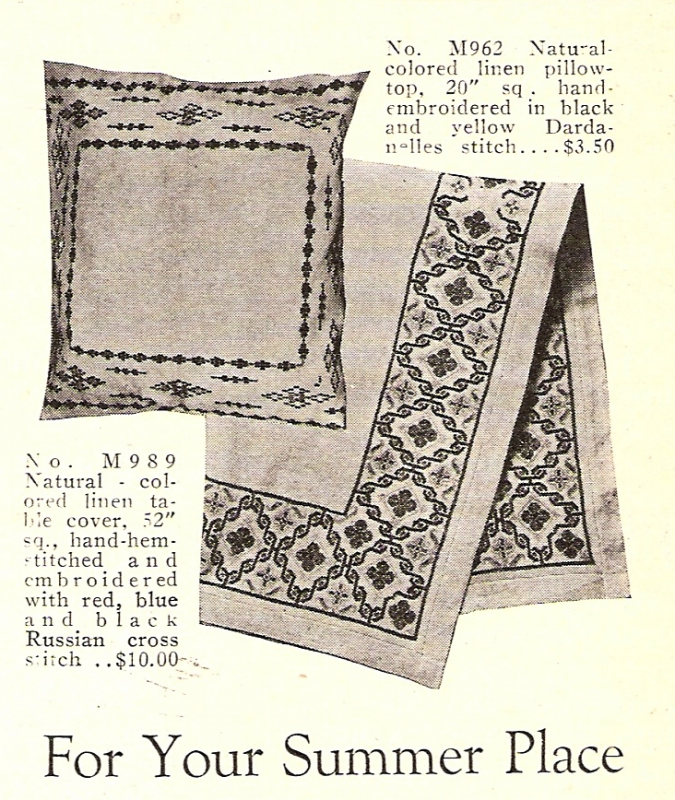

The workers in Syria had a similar story: they had survived the deportations and massacres only to find themselves in a new country without a means of self-support. The women had few obviously marketable skills, but they carried an incredible knowledge of traditional craftsmanship. The confluence of Armenian, Greek, Russian, and Turkish patterns resulted in stunning textiles rich with historical meaning.

Priscilla Capps Hill worked with the women to identify traditional weaving and embroidery patterns. The women were initially eager to mimic the designs that they saw in the bundles of American clothing distributed by Near East Relief.

They agreed to create more traditional crafts to satisfy customers at the Near East Industries shop in Athens, who clambered for embroidered clothing, bags, and linens. Near East Industries workers earned $0.50 per day for their labor. Drawing upon the region’s long history of sericulture, the women worked with locally-made raw and spun silk.

I have hunted through the bazars and museums to trace the original and characteristic designs. Women of Greece are interested in preserving them and have given me every assistance.

Creating a Marketplace

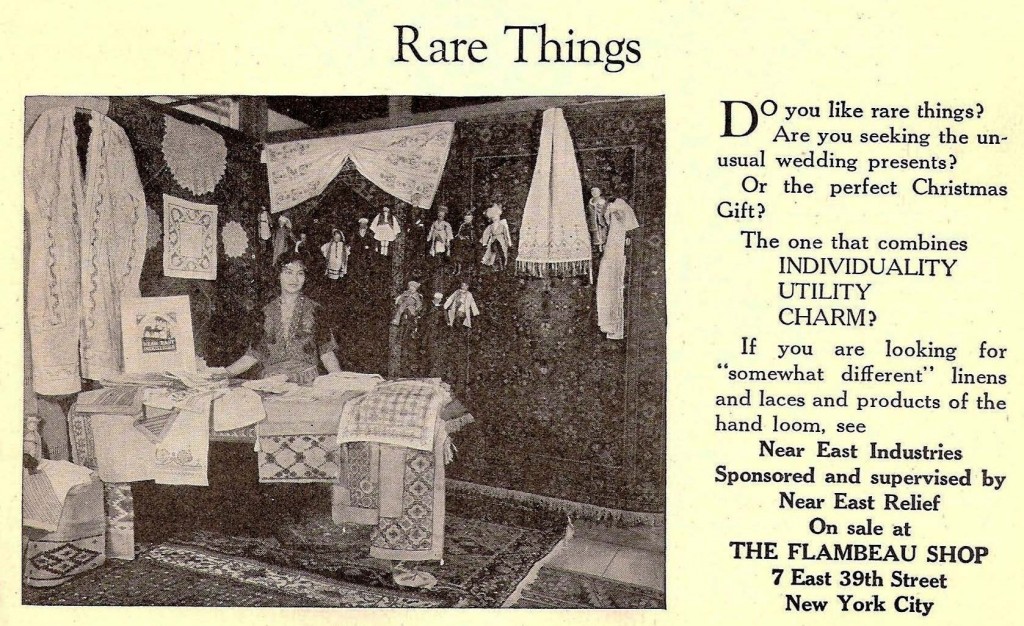

As the American director, Rose Ewald handled all aspects of Near East Industries business stateside. This included the operation of the flagship Near East Industries store at 151 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, which was advertised as “a corner of old Stamboul” in reference to the picturesque area in Constantinople. Ewald supervised a collection of smaller shops in other U.S. cities, including Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia.

Ewald organized seasonal bazaars and special events in New York City. She was also a popular public speaker and a coveted guest at women’s club meetings. Hill (right) made frequent sales trips to the U.S. to promote Near East Industries’ wares.

The inventory grew to include other items made by children in Near East Relief orphanages, such as traditional Armenian Kutahya pottery painted in Jerusalem. Kutahya jars filled with wild thyme honey were advertised for sale in the U.S. Near East Industries also hired women to “make over” donated materials from the U.S. into usable garments. Thus, army surplus bedsheets became dresses for girl orphans. The canvas from old stretchers found new life as sturdy aprons for young cobblers. Unusable sweaters were unraveled and woven into luxurious new carpets.

Every single piece of embroidery that has come to us from the Near East is the expression of an individual woman, loyal to the tradition of her family, village, and race.

Promoting Self-Support

Under the guidance of Rose Ewald in the U.S. and Priscilla Capps Hill in Greece, Near East Industries became a successful business. In 1928 Near East Industries made a profit of $131,371.00 from American sales alone. The Great Depression had a negative impact on sales, but the shops managed to remain open.

As tensions mounted in pre-World War II Greece, Priscilla Capps Hill was adamant about keeping Near East Industries running in Athens; it was the sole source of income for 350 women. She was forced to close the Athens shop in January 1940 due to a lack of tourism to Greece. However, Priscilla maintained that Near East Industries would continue to sell goods in the U.S. “as long as the Mediterranean stays open.” The Hills were forced to flee Greece for Paris in the summer of 1940.

Ewald continued to operate Near East Industries in the U.S. on a progressively smaller scale until her retirement from NEF in 1952. Over the course of 30 years, Near East Industries employed thousands of women — providing them with lifesaving wages, a creative community, and a vocation.

Nearly 100 years later, the Near East Foundation continues Near East Relief’s efforts to promote economic self-sufficiency — but in a very different form.

While Near East Industries focused on traditional crafts, NEF provides business training and micro-financing to facilitate longterm economic advancement. You can meet some of NEF’s entrepreneur’s below.

Meet Some of NEF's Entrepreneurs!

* Like all of the participants in NEF’s Women’s Economic Empowerment & Advocacy initiative in Armenia, Zarik is a survivor of domestic violence. Her name has been changed to protect her identity.

Kutahya pottery made by NER boys and girls in Jerusalem under the guidance of Armenian ceramicist David Ohannessian