Consular Legacies, Part Two: U.S. Diplomatic Records from Persia Show a Nation Buffeted by Stronger Powers and American Support for Persecuted Minorities

Click Below to Explore the Tehran Consulate Records!

For the second part of our collaborative dispatch series with James David, we take a closer look at the fascinating story told by U.S. diplomatic records from Persia. To learn more about the role played by consulates in Baghdad and the interesting information found in the consulate records, read part one, Consular Legacies, Part One: Baghdad Consulate Records Document World War I and Post-War Conflicts and Tensions.

********************************************************************

Decades prior to the proliferation of mass media and the easy spread of information, embassies, consulates, and diplomatic postings were critical for gathering news and sending detailed accounts abroad. For the United States, these postings were especially important as the country became increasingly involved in international politics and humanitarian relief.

Established in 1883, the legation in Tehran was the first U.S. diplomatic post in what was then called Persia. In the following years, consulates were set up in Tehran and Tabriz adding to the overall foreign presence of the United States in the region. Responsibilities included reporting on political, economic, military, and social developments, protecting U.S. citizens, promoting U.S. business interests, and handling immigration matters in the region.

Gordon Paddock was the U.S. consul in Tabriz from before World War I to the mid-1920s. He worked closely with U.S. missionaries and naturalized Americans in Tabriz, Urmia, and other locations in Azerbaijan province to protect their interests and those of the Christian minority communities they lived among. Several times during his tenure he and other western consuls had to flee Tabriz because of threatened Turkish or Bolshevik occupation.

In addition to the U.S. government postings, several religious denominations of Christianity established missions in Persia in areas with high concentrations of Christian minorities. One of the largest of the organizations at the time was the Presbyterian mission in Urmia that served the Assyrians who lived in the region. Beginning in the late 1800s, missionaries arranged for small numbers of young Assyrian men to go to America for their higher education. Almost all later became naturalized American citizens, but many chose to return home to Persia. The missionaries and naturalized Assyrians had a close working relationship with the Tabriz consulate, which served the region more broadly.

William Shedd was the son of Presbyterian missionaries in Urmia. He became a missionary and spent much of his life in Urmia, becoming the key liaison between the Christian community and the U.S. consuls in Tabriz. Shedd died from cholera during the mass exodus of Assyrians and Armenians from Urmia in August 1918

Due to perceived weaknesses in Persia in the early 1900s, Ottoman Turkey, Russia, and Great Britain exercised considerable economic, political, and military influence over the region. Characterized by border disputes and Turkish and Russian incursions into Persia, the region was frequently in conflict. Capitalizing on this weakness, the British and Russian governments entered into a treaty, known as the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, that created delineated spheres of influence in northern and southern Persia. Venture capitalists and industrialists soon exploited the instability in the region and began extracting natural resources. In 1909 the new Anglo-Persian Oil Company, a predecessor to British Petroleum (BP), began large-scale production.

To maintain supplies to the fleet which was converting from coal to oil, the British government took a 50% ownership interest in the company in 1913. It soon deployed British forces in the oil-producing areas and reached agreements with local leaders to protect these vital assets. Russia and Great Britain each controlled one of the two main Persian banks and agreed to divide government revenues in order to repay the large debts the Persian government owed them.

Although not directly involved with the conflict of World War I, Persia was greatly impacted by it. After the start of the war in August 1914, Russian troops soon occupied the Urmia region. Their presence was generally welcomed by the Christian minorities, but strongly opposed by the Muslim majority. In early 1925, the troops withdrew and an Ottoman force, bolstered by Kurds from the mountains along the Persian-Turkish border, entered the area. In an act that would later be considered part of the larger Armenian, Assyrian, and Anatolian Greek Genocide, many Armenians and Assyrians were massacred in their farms and villages.

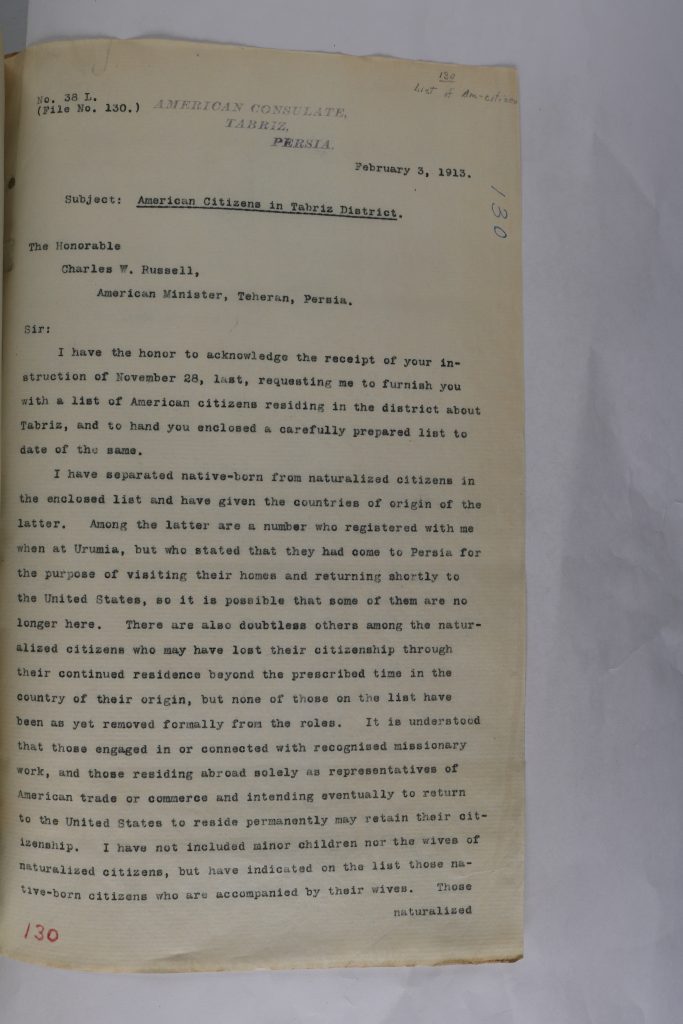

U.S. consuls in Tabriz periodically reported to the Tehran legation the names and locations of native-born and naturalized American citizens in their district. This 1913 letter from Gordon Paddock reported that there were over 80 U.S. citizens.

Fortunate survivors were able to flee to Urmia, where U.S. missionaries did their best to provide relief. American diplomats, exercising their access to resources and lines of contact not available to the average person, contacted various surrounding governments in an effort to protect U.S. citizens in the area and the larger persecuted community as a whole.

During 1916 and early 1917, intense fighting took place between the Russians and Ottomans in many parts of western Persia. The British engaged Ottoman forces in parts of southwestern Persia while driving them to Baghdad, which was later captured in March 1917. America entered World War I in April 1917, but did not declare war on the Ottoman Empire.

The Bolshevik revolution in the fall of 1917 quickly led to an armistice between Russia and the rapidly dissolving Ottoman Empire. Many Russian troops in Persia began looting and assaulting its citizens, particularly Muslims in the area before they left in early 1918. Joined by Assyrians and Armenians fleeing persecution, a fighting force was formed in the Urmia region using much of the equipment left behind by the retreating Russians.

The combined Assyrian-Armenian army fought several battles against local Muslims. The Persian government charged that British, French, and American missionaries and diplomatic representatives in the area were supporting the force, an allegation the three governments strongly denied. However, there was little the Persian government could do beyond lodging protests to end the fighting.

State Department files frequently contain the copies of correspondence with Persian officials in both Farsi and English. This is a July 1923 note from the Tehran legation to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs concerning the legation’s distribution of an American Red Cross donation of $5,000 for earthquake relief in Turbat.

As part of a larger move into the Caucasus, the Turkish army entered Azerbaijan province in May 1918 and quickly occupied Tabriz. Many Christians and foreign consuls posted there fled south. Turkish forces also battled the Assyrian-Armenian army on the Urmia plain. The British military offered supplies and other assistance to the Christians if they could travel to their lines north of Hamadan, but that was not possible.

After several months of fighting, the Turkish army had made it to the outskirts of Urmia. A panic ensued, and large numbers of religious minorities, including many Armenians and Assyrians, fled south to British military lines. Many died from disease or attacks by the Turkish army, Kurds, and Persians before reaching refugee camps established by the British. The several thousand Assyrians and Armenians who remained in Urmia suffered terribly under Turkish occupation.

Shortly after the armistice ending World War I was signed in November 1918, the Turkish troops withdrew from Azerbaijan province. There was an uneasy peace between the remaining religious minorities in Urmia and the local Muslims and Kurds who had once again moved down from their mountain homes. A few American missionaries and Assyrian-Americans returned in the spring of 1919. In May, the Persians and Kurds began fighting one another and the violence spilled over against the Christians. The U.S. consul, who had returned to Tabriz, went to Urmia and led the survivors to safety in Tabriz under the protection of the American flag. The American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, later known as Near East Relief, which had been helping the persecuted minorities in Azerbaijan province since 1916, and other organizations provided assistance to the Assyrians and Armenians in Tabriz and the refugee camps. As before, U.S. diplomats and missionaries were key in the distribution of relief.

Judith David with three of her four children in Tabriz in 1920. Married to another Assyrian, Jacob David, she remained in Urmia with her children and several thousand other Christians during the Turkish occupation which started in August 1918. Her efforts were critical in feeding and housing them under terrible conditions. Her husband and a small number of other Assyrians and missionaries returned to Urmia in the spring of 1919 after the Turks withdrew and tensions lessened. The eruption of Persian-Kurdish fighting in May 1919 and the spillover against Christians led Gordon Paddock, the U.S. consul in Tabriz, to organize an effort to bring all the surviving Christians to Tabriz. The David family never returned to Urmia and immigrated to the United States in 1921.

Bolshevik troops landed on the Caspian shores north of Tehran in early 1920 and briefly threatened to advance on Tehran. They withdrew the following year following a Soviet-Persian treaty normalizing relations between the two countries. The British were now the only foreign military forces left on Persian territory.

Because of an imminent occupation of Tabriz by Turkish or Bolshevik forces, almost all the Christians and foreign consuls there fled to Tehran or south to British military lines late in 1920. Fighting between the Persian government and combined Persian rebel and Kurdish forces in Azerbaijan province prevented the return of the consuls to Tabriz for several years. The Assyrians and Armenians who had fled Urmia and Tabriz during 1918-1920, now forced to live in refugee camps in Hamadan or near Baghdad, sought British and American help in returning to Azerbaijan province. However, the two governments could do very little at first in the face of resistance by Persian authorities to repatriation. Continued exerted pressure and a new Persian government finally resulted in significant numbers of religious minorities and U.S. missionaries returning to the province in the mid-1920s.

The diplomatic records available paint a picture of the pivotal role played by US diplomats and consular officers during and after the genocide. Blessed with a variety of resources, diplomats were able to provide humanitarian aid, advocate on the behalf of persecuted minorities, and encourage a peaceful solution to end the ongoing and violent conflict in the region. We are fortunate to have access to consular records, allowing us a look at the amazing, and often taken for granted, work down by American diplomats in the early 20th century