A Single Thread, Part Two: An Industry Renewed

This is the second dispatch in a series about Armenian textiles. You can read the first installment here.

The aftermath of the Armenian Genocide and World War I brought about unanticipated challenges for the aid workers of Near East Relief. Faced with not only providing homes and caring for thousands of orphaned children, NER was also tasked with somehow giving lifesaving aid for displaced adults left with nothing. By 1921 Near East Relief was one of several organizations working with over 102,000 refugees in Constantinople alone.

A young girl makes lace in a refugee camp, date unknown

The struggle to support so many people was due to, largely, a lack of housing. However, another concern emerged as NER began the complicated work of helping the Armenian, Assyrian, and Anatolian Greek communities rebuild. With so many displaced adults living in refugee camps throughout the former Ottoman Empire that suffered greatly from World War I, steady work was scarce as industries struggled to recover. In addition to the large numbers of unemployed refugee adults, the NER orphanages were filled with children who needed not only a basic education, but skills training for when they were old enough to live on their own.

To meet both of these needs, Near East Relief, led by Priscilla Capps Hill and Rose Ewald, decided to draw upon a skill-set that many refugee women and children already possessed and began to open textile factories throughout the Near East.

To learn more about the work done by Priscilla Capps Hill and Rose Ewald, click here.

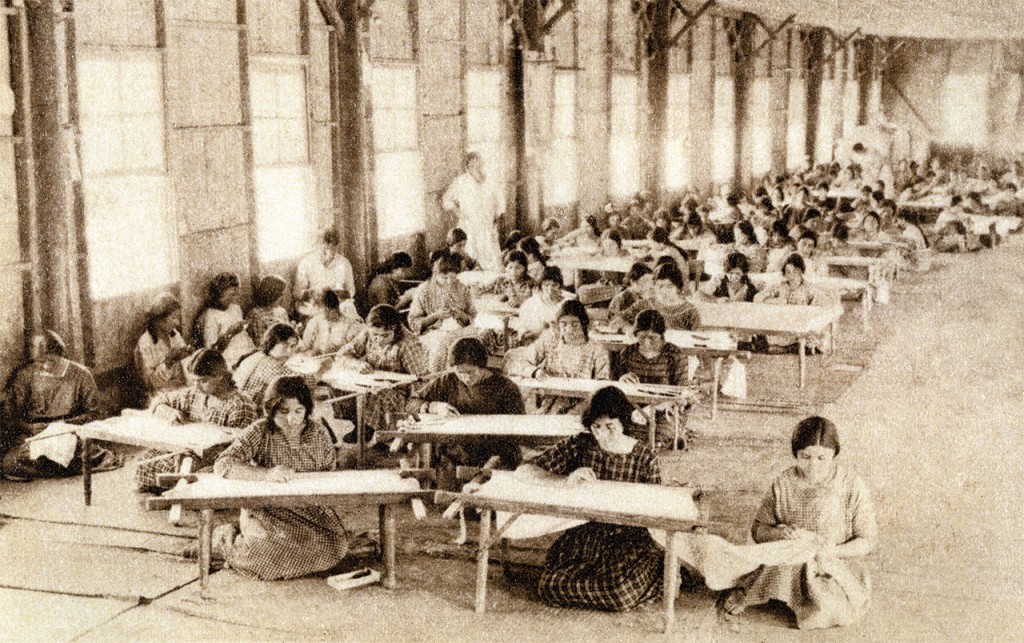

Constantinople (now Istanbul) was known as a tourist destination prior to World War I. As foreigners slowly began to the return to the city on holiday, NER saw an opportunity to not only provide work for women in the city, but also to make money for its continuing work in the area. Employing seamstresses and expert Armenian lacemakers, NER opened a textile factory that made fine clothing and homewares that made for popular souvenirs for tourists.

Young women work at the Fabrica in Constantinople, c. 1921

Elsewhere, NER opened similar factories that specialized in different types of textiles, including clothing, rugs, lace, linens, and a variety of others. Although not the original intention of the relief workers, the opening of factories that focused on traditional crafts helped to preserve the art for future generations while providing critical work for people who needed it desperately.

Stateside, NER opened shops along the east coast that sold textiles produced by refugee women and orphans to Americans who saw the intricate patterns and rich embroidery as luxury items.

Throughout the course of its work in the Near East, NER utilized several giving campaigns that required the skills of seamstresses and weavers. As part of its successful Bundle Day campaign, women working in NER owned factories and small shops took donated clothing that was not useable and turned them into something more suited for the orphans. Nothing went to waste and all clothing that couldn’t be converted into something wearable was unraveled and used in carpets to sell.

As part of its comprehensive work with orphans, NER emphasized developing skills that they could carry with them for the rest of their lives. Although some of the children cared for by NER still had family who were simply too poor to take care of them, the vast majority were left without anyone following the Genocide. This meant that not only did relief workers take on the responsibility of caring for their mental and physical wellbeing, but also ensuring that they maintained a strong cultural identity.

Three young girls embroider together, c. 1921-23, location unknown

Shops were set up in close proximity to orphanages to allow for the young women still living there to work and attend other skills based classes before setting out on their own. These sewing shops utilized traditional methods of hand-sewing and loom weaving, while also modernizing to great effect. While not available for every orphan to use, Singer sewing machines were a critical teaching tool for giving women the skills needed to enter the workforce as textile industries recovered from World War I and rapidly modernized.

Image Left: A young woman uses a Singer sewing machine in a factory, c. 1923-25, Syra

For many women and young girls, the ability to work with textiles was not only a blessing in the form of a steady income, but also a much needed opportunity to embrace and celebrate Armenian heritage in a time of persecution. For older women who perhaps lost their children and families in the Genocide, the opportunity to teach young girls about a centuries’ old tradition was a much needed respite from the harsh realities that came with being a refugee. For the young girls, most of whom were orphaned and left without any means of supporting themselves, learning the art of textiles from older women connected them to and allowed them to embrace a culture that had survived an attempt to systematically wipe it out at a tragically young age.

Image Right: A young woman sewing on a Singer sewing machine, c. 1923

Young girls learning to sew at the Antilyas orphanage, c. 1925

The importance of these industries should not be forgotten. In addition to the work opportunities that changed the lives of over 100,000 Armenian women and girls, NER factories and skills-based training helped in part to facilitate the vital cultural preservation of Armenian textile work.

Today, the Near East Foundation continues the critical work of promoting economic self-sufficiency started by Near East Relief. To learn more, visit: http://www.neareast.org/

The story doesn’t end there!

Check back soon for the final installment of our series on Armenian Textiles.