Strength in Survival: the Girls of Juniyeh

The story of Juniyeh Orphanage is, like so many other Near East Relief stories, a tale of finding strength in survival.

Present-day Jounieh, Lebanon, is part of greater Beirut. At the time of Near East Relief’s activities this area was part of Syria. The city has been known by several names with similar spellings, including Juniah, Juniya, and Djounieh. For the purpose of this Dispatch we will use“Juniyeh.” This is the version that appears most often in the Near East Relief archives. Several other organizations operated orphanages in Juniyeh at the same time as Near East Relief, including the Armenian General Benevolent Union.

A BUSTLING VILLAGE

In the early 1900s, Juniyeh was a bustling port about 10 miles from Beirut, Syria (now Lebanon). The town boasted several silk factories, where highly trained workers practiced the ancient art of sericulture — raising silkworms for their delicate cocoons, which were then harvested and woven into strong, beautiful fabric. The streets of Juniyeh were packed with hundreds of shops. The Juniyeh harbor flourished as the demand for commercial goods and passenger transportation steadily increased. Linked to the large city of Beirut by both rail and sea, Juniyeh was a town on the rise.

Juniyeh was a popular destination for pilgrims based on its proximity to the Shrine of Our Lady of Lebanon. A French-made bronze statue of the Virgin Mary was placed atop a hill in nearby Harissa in 1907. The shrine soon became an important site to the Maronite Christian community, and other religious groups that venerated the Virgin Mary.

World War I swept through Syria, interrupting a period of relative prosperity. By 1920, Juniyeh was a shadow of its former self. Countless residents had fled in the wake of the disastrous famine that accompanied the hostilities. The once-busy streets were quiet. Production at the silk factories had largely ceased. The Shrine of Our Lady looked down upon a ghost town.

ESCAPE FROM THE INTERIOR

A few years later, Near East Relief was desperate for new orphan housing. By 1923, the organization had evacuated more than 22,000 children from orphanages in the Turkish interior. While the majority of the children were transported to Greece under a generous agreement with the Greek government, about 5,000 orphans were brought to Syria.

The large cities of Aleppo and Beirut were already inundated with Armenian orphans and refugees from Turkey, not to mention countless internally displaced Syrians still attempting to recover from the recent devastating famine. New arrivals from the Turkish interior lived in camps on the outskirts of the city. Some lucky children had a roof over their heads, but most of the orphans slept under temporary canopies that did little to protect them from the elements.

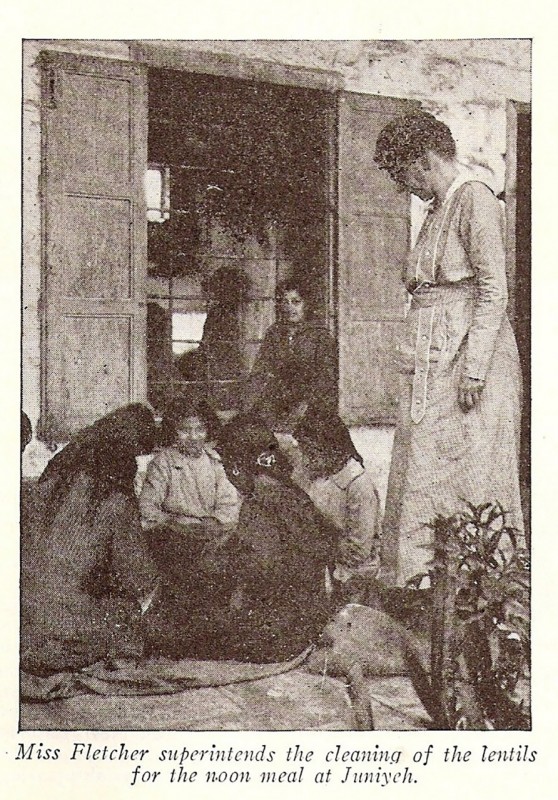

Katharine Ogden Fletcher arrived in Beirut with one such group of girls in 1922 or 1923 (the exact date is unknown). Fletcher had graduated from Smith College in 1900 and earned a Master’s from Columbia University in 1912. Fletcher joined Near East Relief in 1919, and was one of the first Near East Relief workers to enter the region after the Armistice. Katharine Fletcher was stationed at the Near East Relief orphanage in Talas, and then moved to nearby Caesarea. When Near East Relief evacuated the orphanages in the Turkish interior, she superintended the journey of 3,000 children from Caesarea to Beirut — an arduous journey over land and by sea.

Left: Katharine Fletcher watches girls sort lentils in preparation for a meal at Juniyeh.

A NEW GENERATION OF LEADERS

Katherine Fletcher’s charges found a new home in an empty silk factory in Juniyeh. Under Fletcher’s directorship, five hundred orphan girls embarked upon an ambitious experiment in self-government.

The girls were divided into groups of 40. Each group chose a leader to serve a six-month term. The group drew lots to select an adult adviser from the orphanage staff in order to ensure that there was no favoritism. The groups were further subdivided into smaller groups of 10 girls, each with a chosen representative. The small groups were tasked with settling issues and disputes. If they were not able to do so, the group leader would review the problem. The large group leaders also addressed general issues that applied to the entire orphanage community.

The leaders wore coveted uniforms: an American-style dress made from pink, white, and black gingham. The faculty advisers helped the leaders to make policy decisions, but the girls themselves made the rules and designated the punishments. Often the threat of a haircut was enough to deter a girl from behaving badly. One punishment carried particular shame at Juniyeh: to receive old (but clean) clothing when the other girls received new clothing was a mark of extreme dishonor.

Right: A July 1925 New Near East magazine cover featuring the entrance to Juniyeh. Courtesy of Vicken Babkenian.

RUTH NARUMIAN'S STORY

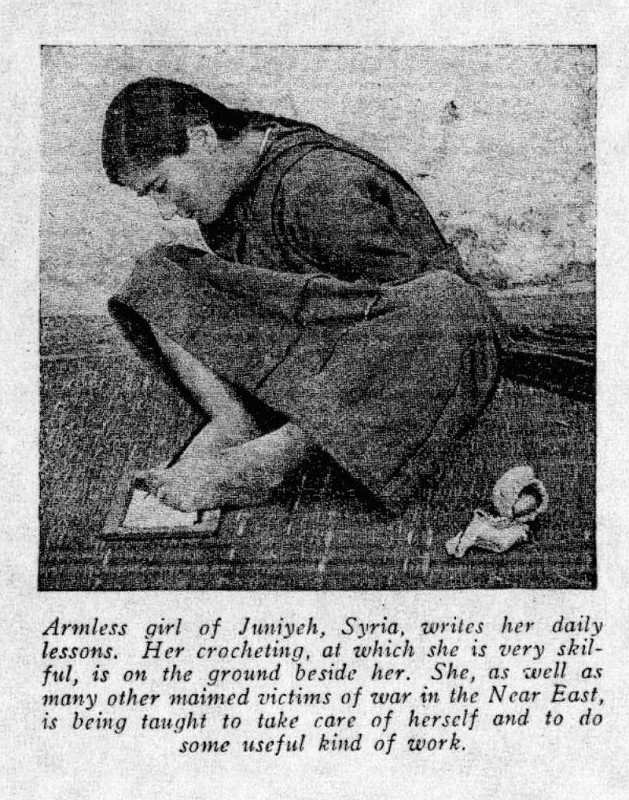

Ruth Narumian of Juniyeh found modest fame in in 1924 when she was written up in a few American publications. Ruth received recognition for her prodigious skills as a writer, seamstress, and crocheter — skills that she acquired at the Juniyeh Orphanage. What set Ruth apart from her companions was that she did not have any arms.

Ruth Narumian had been severely injured as a very young girl. She performed these and all other tasks with her feet. Ruth took the same classes as the other girls at Juniyeh. She became adept at both plain and fancy sewing, and earned high marks for penmanship and drawing. Ruth graduated at the top of her orphanage class.

In October 1924, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that Ruth hoped to attend Vassar College. A group of people had started a fund to help Ruth to pursue a higher education in America, and she was in the process of trying to arrange a visa. Unfortunately, we have been unable to find any other information on Ruth Narumian. Please contact us if you have any information on this interesting young woman!

Right: Ruth Narumian in the New Near East magazine, 1924.

LIFE AT JUNIYEH

Katharine Fletcher finished her term with Near East Relief in 1923. Inez Webster of Galesburg, IL, assumed the leadership of Juniyeh Orphanage. Like their counterparts in other Near East Relief orphanages, the girls of Juniyeh divided their time between school, work, and play.

The girls studied general subjects as well as trades, with a focus on textiles. The girls excelled at “fancywork,” and Juniyeh Orphanage was soon known for its beautiful sewing and embroidery. This was fitting considering that the girls lived and worked in a former silk factory!

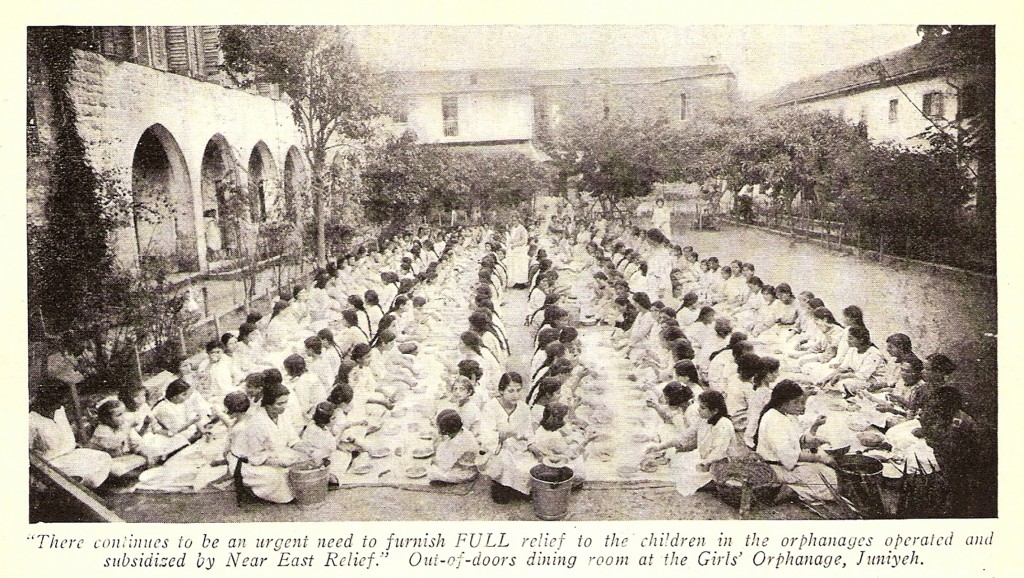

In their spare time, many of the girls built playhouses from found materials in an open area used as a playground. Music was a very popular extracurricular activity, and many girls chose to sing in the choir. The girls’ choir of Juniyeh gave concerts with the boys’ orchestra of Jubeil. Because space was at a premium at the orphanage, the girls dined in a large outdoor dining area.

A 1927 diary entry from Near East Relief official Barclay Acheson mentions a brief visit to Juniyeh en route to Ghazir. Acheson reports that “there are 99 girls [at Juniyeh], doing good needlework.” He also writes that the orphanage was largely supported by Beirut’s Armenian population, and that an Egyptian group that had previously funded the orphanage was no longer doing so. By this time, all Near East Relief orphanages were focused on outplacing orphans into homes and careers. Juniyeh probably closed its doors by 1928.