The Armenian, Assyrian, and Anatolian Greek Genocide: What Is Genocide?

In our last Dispatch we asked some fundamental questions about the Armenian Genocide. This particular question merits further exploration.

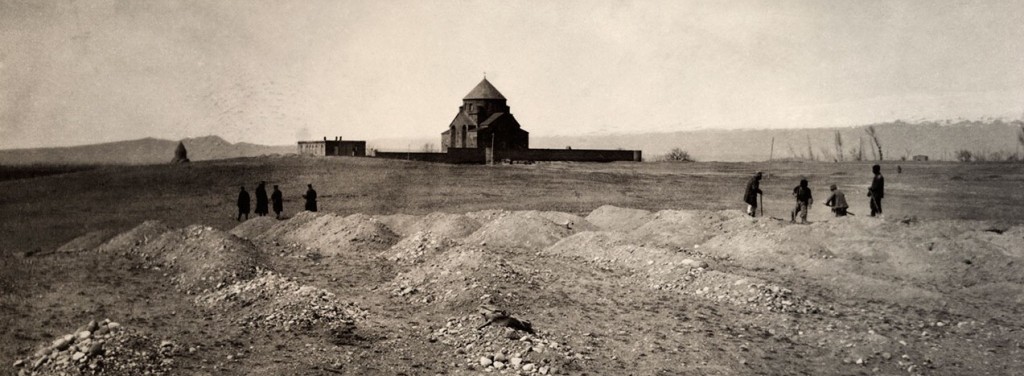

Refugee burial ground at Etchmiadzin, 1919. Courtesy of National Geographic archives.

This is the second in a series of Dispatches on the Armenian Genocide. You can read Part 1 here.

A CRIME WITHOUT A NAME

In August 1941, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill informed rapt radio listeners that Europe was “in the presence of a crime without a name.” Churchill spoke of the Nazis’ systematic annihilation of the Jewish people — the true extent of which would not be known for four more years.

That same year, a refugee named Raphael Lemkin arrived in the United States. Lemkin was granted entry to the country in part because of his impressive credentials. Lemkin was an accomplished Polish attorney: he had lectured internationally and helped to codify the first penal code in post-World War I Poland. As early as 1933, Lemkin had approached the League of Nations with a proposal to outlaw “acts of barbarism” as a crime under international law.

Lemkin had been inspired by his research on the massacres of Ottoman Armenians from 1915 -1923 — research that he approached from a legal perspective as well as a historical one. When Lemkin made his proposal to the League of Nations, the atrocities against the Armenians were still relatively fresh in international memory. The August 1933 Simele massacre of Assyrians in northern Iraq cemented Lemkin’s beliefs. He argued instances of targeted barbarity must be recognized as criminal acts, and subject to punishment within an international justice system.

Lemkin was also a Jew. He had seen his career as a public prosecutor cut short by anti-Semitism. He had fought with the Resistance movement, but ultimately fled Poland for Sweden when his home country fell under the grip of Nazism. Within a few short years, Lemkin would lose 49 family members to the “crime without a name.”

Raphael Lemkin gave this crime a name. He called it “genocide.”

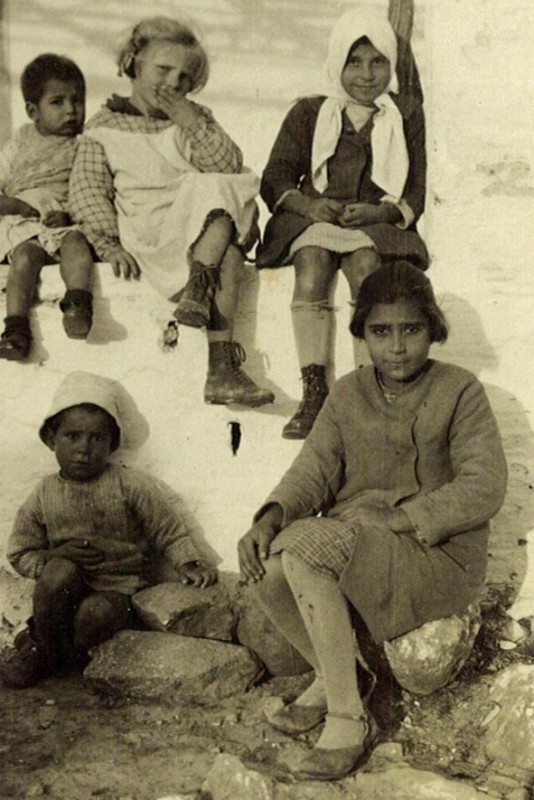

An Armenian refugee community in the Caucasus region, c. 1920.

CREATING A LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Raphael Lemkin published Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress in late 1944. He introduced genocide as a legal concept in that book.

For all of history, the killing of one person had been called murder. The killing of a group of people had been mass murder. Large-scale acts of murder had been described as massacres or atrocities. There was no word to describe the killing of a large group of people based on their culture, religion, or ethnicity. Lemkin created the word “genocide” from the ancient Greek word genos, meaning “race, tribe, or people,” and the suffix -cide, from the Latin verb caedere, meaning “to kill.”

Lemkin defined genocide as “a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.”

Lemkin also clarified that genocide is not limited to physical acts. It includes the psychological traces that are left behind when one group of people attempts to systematically destroy another. Genocide can occur in times of war or peace.

Young man with a cross. He is probably an older Near East Relief orphan or a graduate. Date and place unknown.

The United Nations drew upon Lemkin’s work when creating the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) in 1948. Article 2 of the CPPCG defines genocide as:

“any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

INTERNATIONAL OPINIONS

The United Nations opened the CPPCG for signatures on December 11, 1948. The United States signed on that day. The Turkish government accepted the CPPCG in July 1950. The Convention came into effect on January 12, 1951.

In 1996, in the wake of genocidal acts in the former Yugoslavia (1992-1995) and Rwanda (1994), Dr. Gregory H. Stanton presented a briefing paper to the U.S. State Department outlining eight stages of genocide: classification, symbolization, dehumanization, organization, polarization, preparation, extermination, and denial. Stanton later added discrimination and persecution to the list.

Two years later, 120 countries signed a treaty creating an independent court to address serious crimes in the international community. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has jurisdiction over allegations of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes of aggression against a State.

The ICC adopted the definition of genocide as written in the CPPCG. The ICC Prosecutor can also initiate investigations based on information from individuals, State Party governments, the United Nations, or other organizations.

The genocidal campaigns in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia took place before the creation of the ICC, and were therefore prosecuted by International Criminal Tribunals at the Hague.

Denial is the final stage that lasts throughout and always follows a genocide. . . [The perpetrators] deny that they committed any crimes, and often blame what happened on the victims.

RECOGNITION AND COMMEMORATION

There is a large and active scholarly community devoted to the study of genocide. The International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) has issued three resolutions recognizing the atrocities that took place in the Ottoman Empire from 1914–1923 as genocide. The most recent resolution, issued in 2007, includes Anatolian and Pontian Greeks and Assyrians as victims of the Ottoman genocide.

By 2014, 21 countries had officially recognized the Armenian Genocide. Seven more governments and the Catholic Church recognized the Armenian Genocide in 2015. The United States government has not officially recognized the Armenian Genocide, although 43 states have recognized it by proclamation.

The Turkish government maintains that the events of 1915 – 1923 do not qualify as genocide because there was no “intent to destroy” as required under international law. Many officials state that the massacres were actually military activities, and that the dead were casualties of war. Some maintain that Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks were “relocated” because they were a security threat to the Ottoman Empire; others argue that minorities were resettled for their own protection.

There is a growing movement among Turkish intellectuals to recognize the events of 1915 – 1923 as genocide. Each April, groups hold commemorative events in small towns and large cities throughout Turkey. The events draw more supporters every year.

Genocide casts a long shadow. As Raphael Lemkin so sensitively observed, the people who lose their lives are not the only victims. Genocidal acts leave deep scars on individuals and on entire cultures.

The little girl who grew up in an orphanage, never knowing the name that her parents gave her, is a victim of the Armenian Genocide. The young man with vague childhood memories of a different family, a different language, a different faith, is a victim of the Armenian Genocide. The woman who lived through the deportations, but saw her family die is a victim of the Armenian Genocide.

These are the people who, against all odds, preserved a culture. They are mothers, fathers, grandparents, great-grandparents, friends, neighbors, teachers.

They are survivors. The Near East Relief Historical Society honors them — on April 24, and every single day of the year.

(c) 2016 The Near East Foundation