Museum Detectives, Part 3: A Detective’s Epiphany

When I, your faithful and inquisitive Museum Detective, last checked in, I was almost sure that I had solved my photographic mystery. I had looked at maps and photographs from Smyrna in the early 1920s. I was confident that I had identified a vantage point on the shore where a photographer could capture a waterfront, aqueduct, and hilltop fortress in a photograph.

But was I seeing what I wanted to see?

At last, the mystery is solved!

Check Your Assumptions

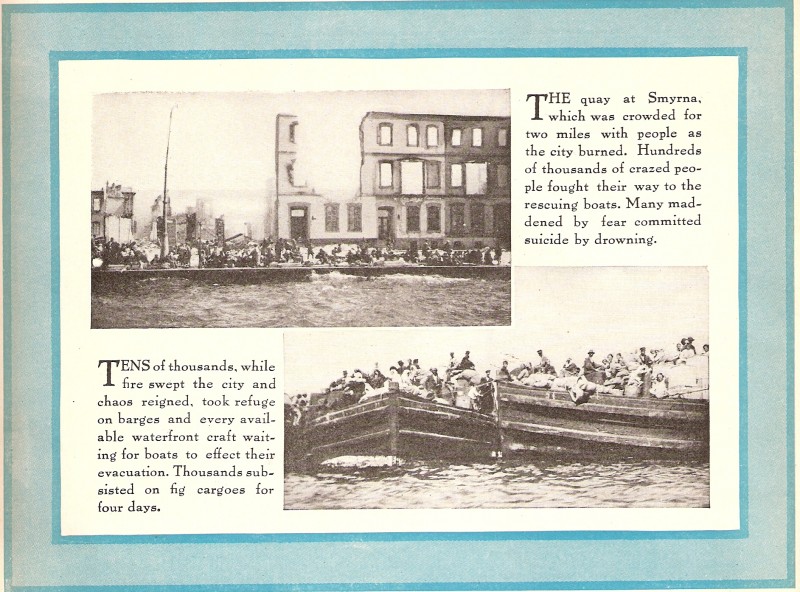

Assumptions just might be the natural enemies of thorough research. In my work, I have looked at dozens of photographs of the burning of Smyrna. I’ve looked at photographs of the flame-ravaged city taken from ships in the harbor. I’ve seen post-fire photographs of ruined buildings, and of refugees clamoring for spots in a handful of rescue boats. Assumptions had taken root in my brain.

I’m prepared to let you in on a secret. Try though we might, curators are not always completely objective. We make assumptions just like anyone else looking at a photograph for the first time. Sometimes we are even hindered by our background knowledge. I assumed these were photos of Smyrna based on what I knew about Near East Relief and Smyrna. The destruction of that city, and the subsequent refugee crisis, were formative events — not just for Near East Relief, but for global history. It was a convenient explanation for an archival mystery. It would be very exciting to find close-up of the Smyrna aftermath in our own archives. But there were a few nagging questions poking holes in my hypothesis.

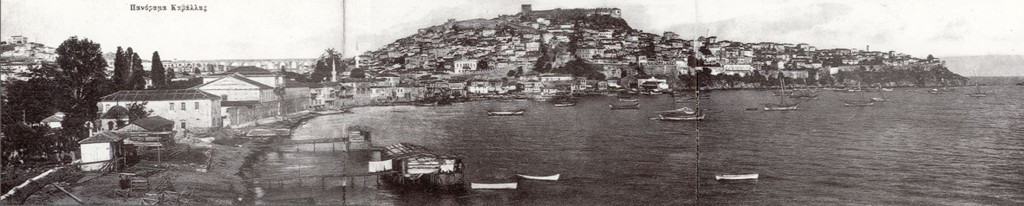

In the process of my research, I revisited this image (right) from the back cover of the October 1922 New Near East magazine. It raised a seemingly obvious question that had never crossed my mind: if my mystery photos were from post-fire Smyrna, where were the ruins? The fires that ripped through Smyrna in September 1922 left the city in shambles. Grand buildings became burned out shells overnight. The thriving port was reduced to cinders. The waterfront of the city in my mystery photograph (above) may be crowded, but it is tidy — no singed buildings, no rubble, no indication of recent tragedy.

Kizilcullu aqueduct, Smyrna (Izmir). Original image courtesy of the Levantine Heritage Foundation (www.levantineheritage.com)

My Theory Falls Apart

Once I started asking myself challenging questions, my Smyrna theory proved to be very shaky. Remember how excited I was about the aqueduct in the mystery photo? It seemed like such a great clue! I was sure it was the Kizilcullu aqueduct near Paradise, a suburb of Smyrna. I found several excellent photographs of the Kizilcullu aqueduct at the Levantine Heritage Foundation website.

In fact, they were so excellent that I was able to determine that my aqueduct was definitely not the Kizilcullu. They just didn’t match up. The aqueduct from the mystery photo (left) has a distinctive pattern of large arches alternating with two smaller arches stacked on top of each other. The Kizilcullu does not have any stacked mini-arches.

...And Falls Apart Some More

As long as we’re questioning our assumptions, let’s scroll back to the top and look at that crowd again. It’s all men, and maybe a few boys. I don’t see any women or girls in the three photographs. The men are wearing nice-looking coats and hats (see detail, right). In fact, when I recorded my first impressions of the photos, I described them as “well-dressed.” The scene has a very orderly feel.

The quay at Smyrna after the great fire would have been anything but orderly. In the immediate aftermath of the fire, tens of thousands of people mobbed the waterfront. Over the next two years, Ottoman Greeks awaiting mandatory resettlement in Greece lived as refugees in the wreckage of Smyrna. Families — men, women, and children — clustered in makeshift dwellings as Greece and Turkey exchanged minority populations. It was a devastating time period.

My mystery photographs show a scene that is nowhere near as harrowing. The men standing in the water certainly look cold, but I would not describe them as angry or frightened. In the very first photo we looked at, some of the men are even smiling. The overall mood of the photographs is more solemn than stressful.

As if on cue, a new message pops up in my inbox. The secretary of the Levantine Heritage Foundation has gently but firmly dispelled my Smyrna theory for good. He says that there is indeed a set of aqueducts outside of Izmir (formerly Smyrna), but they are far enough inland that they would not be visible from the water. He also tells me that Mount Pagus is not so close to the seashore either, and that the wall of the fort does not extend down the hillside. Lastly, he notes that the arc and texture of the shingle beach does not match up with the shape of the Izmir coastline.

But the news is not all bad. The secretary has an educated guess as to where the photographs were taken, and he’s included some helpful links.

The beautiful shoreline of Kavala, Greece. Image courtesy of www.kavalagreece.gr.

Welcome to Kavala!

It turns out I don’t have to start from scratch. A quick trip to the website for Kavala, Greece (website is in Greek), and I’m confident that the secretary has steered me down the right track. This photograph of historic Kavala (above) has everything I’m looking for.

Kavala is port city in northern Greece. Known in antiquity as Neapolis, and later Christopoulos, Kavala has a long and rich history. A Byzantine fortress overlooks Kavala from the top of Mount Pangaeus. An aqueduct with a distinctive arch-double arch pattern sweeps down from the mountain and through the city. The aqueduct was built in the 1500s, when Kavala was part of the vast Ottoman Empire. The structure probably replaced an earlier Roman aqueduct. Popularly known as the Kamares (“arches” in Greek), the aqueduct is a beloved Kavala landmark. The large white buildings in my mystery photos were probably warehouses — possibly tobacco warehouses, because Kavala was an important center for the Greek tobacco trade.

Near East Relief was active in Kavala after the Smyrna disaster. The organization resettled thousands of orphans in Greece, thanks in no small part to the help and generosity of the Greek government. A New Near East magazine article from June 1923 tells us that Kavala was chosen as an orphanage site because it was an ideal place to teach farming. Near East Relief leaders also appreciated the city’s biblical connection: Kavala was popular with pilgrims, who followed the route of the Apostle Paul through Greece. By December 1923, there were 2,000 children living in the Near East Relief orphanage in Kavala.

A Detective's Epiphany

Now that we know where we are, what is going on in our pictures? The answer arrived in the form of a news story: the Greek Orthodox community in Izmir (formerly Smyrna) celebrated Epiphany on January 6, 2016. This marked the first official celebration of the holiday in that city since the burning of Smyrna.

Epiphany, which marks the birth and baptism of Jesus, is often accompanied by a Blessing of the Waters. Many Orthodox Christians around the world celebrate Epiphany by immersing themselves in a lake or river. Greek Orthodox communities perform an additional ritual called Diving for the Cross: a priest tosses a cross into the icy water, and local men dive in to retrieve it. The tradition is observed throughout Greece, including a large celebration in Kavala. Epiphany continues to occupy a special place in the Greek Orthodox calendar as a day of reflection and renewal.

The men in our photographs were probably gathered on the Kavala shoreline in preparation for the Epiphany celebration. What this Museum Detective initially took to be a scene of crisis is actually an occasion for great joy.

And just like that, our mystery is solved.

But it doesn’t have to end here. You can be a Museum Detective with your own family’s historic materials. Haul out those photo albums and shoeboxes, and try looking at them through different eyes. And don’t forget, you can always share your Near East Relief-related photos and documents with us for inclusion in the digital museum!

Signing off for now,

Molly Sullivan

Museum Detective

(and NERHS Director/Curator)

Share Your Stories With Us

Men in Kavala, Greece celebrate Epiphany, 1920s.