In Five Images: Music in the Orphanages

The biggest curatorial challenge is deciding what to show people. Every image tells a story, but it’s impossible to give each image the same level of visibility. The “In Five Images” series offers a quick look at some of the things that you might have missed.

"Shall the Near East Have Music?"

A Near East Relief pamphlet from the 1920s asked the question, “Shall the Near East Have Music?” The answer was a resounding “yes.” Musical education was not just entertaining — it provided the children with a creative outlet and preserved cultural heritage.

An outdoor music lesson at Alexandropol. The boys are playing long-necked lutes, or saz, an ancient Central Asian instrument.

Songs of the Open Air

Most Americans knew that the Armenians were Christian, but their knowledge of Armenian culture ended there. The New Near East magazine helped to acquaint American subscribers with Armenian life, including music and poetry.

The October 1921 issue stated that the Armenians as “a nation are lovers of music and poetry . . . According to their belief, the art of an ashough [a minstrel or troubadour] was a special divine gift, given only to a chosen few.”

The popular Armenian author Arshag Tchobanian described Armenian music and poetry as “the art of a nation whose home is in the mountains — that is to say, an art of the open air.”

Armenian folk music sounded distinctly exotic to American ears. Traditional Armenian music is based on a seemingly endless scale, as opposed to the familiar octave (eight-note) European scale system. The instruments were familiar in appearance, but very different in sound.

The Sounds of Armenia

Armenians have been playing the ancient double-reeded duduk for well over one thousand years. Made from aged apricot wood, the duduk produces a haunting melody and is often played in pairs. The sound is compared to a clarinet, but is completely unique.

The oud also plays a prominent role in Armenian folk music. This string instrument is similar in construction to a guitar or lute. The large, pear-shaped body creates beautiful resonance with each note. The construction of these historical instruments was an art form in and of itself.

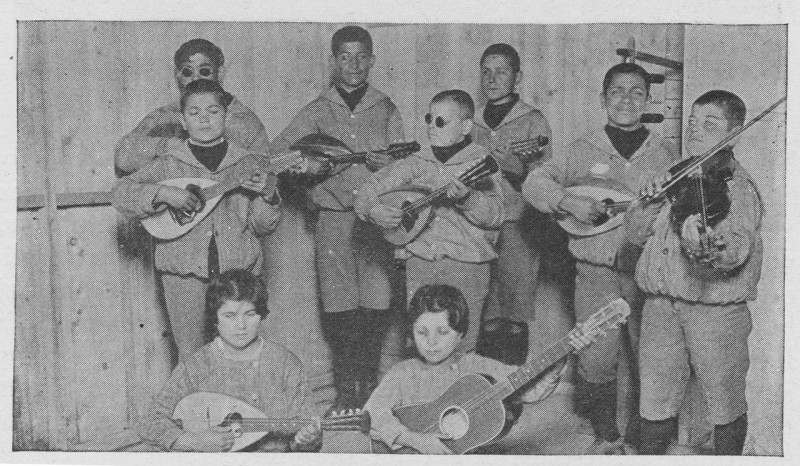

Playing for Their Peers

Many children had lost all or part of their vision as a result of trachoma, a highly contagious eye disease. Blind children received musical instruction, as did their sighted peers. Every orphanage had at least one orchestra.

The Blind Boys’ Orchestra of Aleppo was particularly popular. The orchestra played frequent afternoon concerts for children and hospital patients, a practice that was no doubt rewarding for both musician and listener.

In their music one often hears the song of the shepherds reverberating across the deep valleys, and repeated by its many echoes. It is . . . the most perfect of poetic works.

Song and Dance

Girl orphans were less likely to study musical instruments, but singing and dancing were vital playtime activities. Each day included scheduled recreational time. Armenian circle dances are as old as the culture itself.

As in many cultures, Armenian group dances are a means of celebration and self-expression. What the girls lacked in traditional colorful costumes, they made up for with enthusiasm.

The Near East Relief film Alice in Hungerland shows young Armenian girls entertaining Alice, their American guest, with traditional dances — much like this photo from Alexandropol.

Making New Traditions

Children also learned to play instruments like flutes and trumpets donated by American well-wishers. Orphanage bands greeted tourists with rousing renditions of American melodies. In 1930, Near East Relief co-founder James L. Barton wrote that “Every American traveler who has visited the orphanages in the Near East within the last six or eight years has been welcomed by a band or orchestra, playing diligently, and with no uncertain sound, on contributed American instruments.” “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” were perennial favorites for American audiences.

Barton also describes two orphans who achieved fame through music. Gregor, a boy from Polygon Orphanage, received violin lessons as part of his vocational education. Gregor later became a soloist in a well-known blind orchestra in Moscow. A girl from Seversky Post (sadly unnamed by Barton) was known throughout the orphanage community for her beautiful singing voice. She attended the National Conservatory for Music in Erivan (now Yerevan) and became a distinguished singer in the Caucasus region.

An orphanage orchestra playing American instruments bids a fond farewell to American visitors, c. 1921.